- Home

- George Zebrowski

Cave of Stars (Macrolife Book 2)

Cave of Stars (Macrolife Book 2) Read online

EARLY BIRD BOOKS

FRESH EBOOK DEALS, DELIVERED DAILY

BE THE FIRST TO KNOW ABOUT

FREE AND DISCOUNTED EBOOKS

NEW DEALS HATCH EVERY DAY

Cave Of Stars

George Zebrowski

Praise for Cave of Stars

“When people call science fiction the literature of ideas, they’re talking about George Zebrowski. Cave of Stars combines ruthless intelligence with genuine drama and suspense, making it one of Zebrowski’s best.”

M.J. Engh, author of Arsian and Wheels of the Wind

“Cave of Stars, a companion volume to Zebrowski’s acclaimed 1979 novel Macrolife, is an extremely thoughtful book…vivid characters personalize and enliven time-worn debates about faith and reason, tradition and change, responsibility and individual autonomy…a future of wonder and menace and infinite possibilities reminiscent of Ursula le Guin’s Hainish novels, lain Banks’s cultural novels (though Macrolife preceded them by a decade)…a suspenseful space adventure. Thought-provoking ideas. Stuff blowing up. What more could you ask?”

Curt Wohleber, Science Fiction Weely

“Another fine novel. Zebrowski has always thought more deeply about important matters than do most other science fiction writers and [Cave of Stars] is a strong indicator that he is still using his considerable intellectual and artistic talents to the fullest.”

New York Review of Science Fiction

“An entertaining tale of human aspirations that reasonably portrays the jousting between faith and science that is likely to be as much a part of the future as it has been of the past.”

Washington Times

“A thoughtful and thought-provoking novel…very good in drama and spectacle departments, as well. The story takes surprise turns. I tell you, George Zebrowski is not to be trusted. He’s dangerous to minds too used to cliches and stereotyping.”

The Ceis Letter

and praise for GEORGE ZEBROWSKI’s BRUTE ORBITS

“Fascinating…one of the futuristic thought-books of the year.”

Ian Watson

“A wonderfully inventive novel…capturing much of the sense of awe about the universe that is one of the major lures attracting new readers to the genre.”

Science Fiction Chronicle

“A brilliant and dramatic philosophical reflection on the nature of society, technology…and humanity itself. Zebrowski is a deep thinker who writes about the ‘big questions’ in the grand tradition of Wells, Stapledon, and Clarke.”

Jack M. Dann, award-winning author of The Silent and The Memory Cathedral

“Zebrowski never ceases to invest his individual characters with three-dimensional roundness. Startling and sobering, Zebrowski’s provocative novel should prick the consciences of all readers, as he slices open the veins of prisoners and warders alike, revealing the identical blood that flows on either side of the bars.”

Paul Di Filippo, Asimov’s Science Fiction

“An impressive look at the penal system of the future. The author explores this…through a number of credible characters and demonstrates once again our ability to commit heinous crimes in the name of the common good. Highly recommended.”

Don D’Ammassa, Science Fiction Chronicle

“Zebrowski conflates savagery and mercy, conflates his vision of penology and salvation in ways which I’ve never before seen in science fiction. This sad and wise novel with its souls of ice and fire circling Earth in untended isolation, refracts the eternal drama of retribution and expiation. Crime and Punishment by Stapledon.”

Barry N. Malzberg, award-winning author of Beyond Apollo

“Boldly speculative. Zebrowski argues his points with conviction.”

Publishers Weekly

“A strong, thought-provoking work. Zebrowski has crafted an impressive narrative voice that is distanced enough to deliver authoritative, omniscient exposition, yet flexible enough to segue smoothly into each character’s point of view.”

Marcos Donnelly, author of Prophets for the End of Time

For Barry Malzberg, Cassandra’s lover,

Who also instructs Athena and Apollo.

“The life of reason is our heritage and exists only through tradition. Now the misfortune of the revolutionists is that they are disinherited, and their folly is that they wish to be disinherited even more than they are.”

—George Santayana

“Reason’s heritage exists only through a flawed tradition, and can everywhere be seen subverted. The good fortune of revolutionaries is that they are disinherited, and their salvation is that they seek to be even more disinherited.

The past should be remembered if it is still at work in the present, for good or ill; but if it is all used up and has nothing more to say to the present, then it cannot summon the future and should be forgotten.

What may be left of it is a kind of dramatic beauty which elicits from us a painful love of the past, a love that also imagines some hidden wisdom or virtue is still there; but what remains is only a memory, or a false memory of things once familiar but now gone. Will our futures go the same way of impermanence? We shall see.”

—Richard Bulero Against the Past

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

1

All this began some twelve light-years from the Sun, in the year of 2331, on the fourth planet of Tau Ceti, in the third century after the death of Earth.

2

Warm wind threw salt spray into Ondro’s face. Dark clouds stabbed the sea with lightning. Rain swept across the reef, raced the breakers and dotted the half-moon beach with a million drops. He held his face up to the wash, inhaling land odors from the shower, imagining the continent where all that would have been his went on without him.

He had taken to going out to the beach just before a storm, to be alone when reproaching Josepha

. Are you alone now, my love? Do you suffer for what you did? Had she done anything?

He sat down as thunder rolled over the sea. A bolt burned the sand near him, but he felt only a feeble fear at its illusory show of purpose. Those who had arranged his end would not be so easily cheated. The lightning seemed to know enough to avoid that. It both amused and dismayed him that the other exiles preferred inevitable drowning later to a quick, merciful bolt sooner. Hope breathed beneath their daily resignation. They could not help it. What was reason, after all, but a gray counsel. Tomorrow the ocean might dry up and they could all walk home—and be met halfway by white horses to ride the rest of the way.

He clenched his teeth and shook with the sudden tropical chill as low clouds pulled in over the island. He shivered into sorrow, then lay back and stared up into the hurrying gray masses, seeing Josepha and himself in their first moments together, regarding each other with interest, even wariness, as if each already knew what was to come—she looking tall and slim, long dark hair down her back, he stocky, light-haired, healthy—and felt love for their shy innocence, and despair for the wreck of himself now, for what she was now. Kill me today, he said to the approaching storm. Today.

Her disappearance a week before his arrest, her failure to search him out in prison, had convinced him that she had been a loyal cleric’s daughter. Her dark-eyed looks of devotion and tender words had been false from the start, his love for her a leash placed around his neck by the secret police; and instead of the consummation of a marriage night, he had been given only the memories of longing for her pale body.

They had met in their first year at New Vatican University, among the sons and daughters of the professional class—merchants, artisans, engineers, lawyers, and physicians—who had come for their grudging chance at learning, even though their choice of professions was restricted to that of a student’s parents.

He had trained in architecture and had planned to return as his father’s apprentice. Josepha had studied theology and moral law, hoping to become a lawyer. She had told him that she was being sponsored by a papal official who wished to remain anonymous. Later, she had confided to him that this official was probably her father, but he had been skeptical; the illegitimate children of clerics had been known to make exaggerated claims about their anonymous fathers in the hope of advancement.

In their second year, Josepha had drawn him into a clandestine group that had access to the restricted papal library, where he had learned something of Earth’s history, and had come to believe that the papacy had to be abolished, by force if necessary. The very existence of the concealed library, cut out of the rock beneath New Vatican, had convinced him of the urgent need for change. Knowledge that could change the world for the better had been hoarded for three centuries. There was no need for people to work so hard on farms and in the townships. A better and longer life was possible. The endlessly repeated idea of a difficult daily trial as preparation for a life beyond the world began to seem cruel to him, and his faith had been replaced by contempt for the Church. The life it had made for its people was the Way of the Cross, with no reward but death for the common man, while the elite enjoyed temporal power. The fact that the library could be penetrated had convinced him of the regime’s fatal weakness.

At the center of the papal library sat a duplicate of the control room from the starship that had brought the original refugees from Earth. The ship itself had been left in high orbit around Ceti IV, but the duplicate control room had been built to transfer from orbit the ship’s artificial intelligence and database. Yet millions of books had never been printed out and could be viewed only on aging equipment. The corridors around the central bank were filled with thousands of hastily bound volumes that had been retrieved as they were needed, or as a hedge against failing information storage, or because a cleric had become curious. Pornographic volumes lay tucked away here and there, and sometimes, when Ondro looked for them again, he found they had disappeared. His overwhelming first impression had been that almost no one knew what was in the library anymore and that this amnesia would one day become complete. No one knew if the artificial intelligence still spoke to anyone, but he doubted it; the heavy door to the central control area was locked, and it appeared not to have been opened in many decades.

The official doctrine of the Church was that slow changes were best. The catastrophic example of Earth’s brief technological history was to be avoided by educating only a small technical class that would maintain a stable economic government under the Church’s moral guidance. In practice, the official doctrine of change meant no change at all.

The library group became a revolutionary cadre at the end of the second year, when Ondro’s brother Jason had arrived, but its only aim was to continue learning against the day when the papacy could be brought down. The creation of effective cells that would include members in high positions would take many years, perhaps longer than the lifetimes of the original members.

“We’re being too cautious,” Jason had said one day. “We should strike at the top as soon as possible, take their lives with one blow. They’ve been secure so long that it will come as a shock, and before they can rally we’ll have control.”

“But what if public support fails?” Josepha had asked.

“The public will know nothing about it. We’ll simply replace the gang at the top, and the others will follow, scarcely realizing there has been a change. Then we’ll start replacing from the top down, keeping our group a secret, so that we can continue no matter what happens.”

It had all been so halfhearted, Ondro realized with a renewed dismay as he sat in the downpour. Renunciation was the only balm left for his regrets and lingering ambition. Here there was no future to build, no past to tend. The night’s starry immensity seduced him into a sublime self-sufficiency, and by day the sunlit intimacy of trees, sand, and water lulled him into forgetfulness.

But a durable peace eluded him. Thoughts of death brought back the icy resolve of his first convictions. He still wished for the end of Bely’s theocracy, the death of Bely himself, if necessary, and would gladly plot again if he were ever given a place from which to strike.

But that place was not here. These islands were only sandbars. Sooner or later a hurricane would sweep the entire archipelago clean of life, as it had done in the past. Josephus Bely, His Holiness Peter III, who hid the knowledge that would topple him inside a rock, had chosen these islands as the final place for both criminals and political exiles, where the great sun-engine of weather would do his killing for him.

3

The whispering snake had coiled in Josephus Bely’s sleeping brain for nearly twenty years. The end is coming, it hissed. He opened his eyes to darkness and hated his bodily decay, because it strangled his faith in the life to come. The end is coming!

And it would be final. The hope that had made him deathless during his youth of faith was fading, and he feared that this growing faithless emptiness within him was a punishment for the lingering imperfections in the papal succession from Old Earth, and for the changes—the changes, the poison of the changes that seemed to come with a wind from hell!

He struggled up from his bed and crossed the cavernous room to the open windows. Great white clouds sat over the sleeping city of two-and three-story wood and brick buildings that huddled around the open spaces and tall towers of the palace and cathedral.

He stepped out on the terrace and filled his lungs gratefully with the night air. There is a life beyond this one, his tingling body said as it was chilled by the brine-spiked breeze from the western ocean. The changes, the mortal changes, his mind insisted, they have destroyed you! All clerics, including popes, had fathered sons and daughters by selected females at one time, to increase the numbers of the refugees from Earth. According to the Jesuit geneticists, the arriving community had been just large enough to survive; to hold back any reproductive potential would have needlessly limited the gene pool’s diversity. The women’s faces had been covered

at first, so that no cleric would know his offspring.

But in his time he had known his daughter’s name, fathering her with a Sister of Martha long after he had become bishop. The anonymous reproductive duty of novices for the priesthood should never have been extended beyond the time of ordination. The personal need had lived beyond the immediate one of community survival because the geneticists had only made temptation easier to accept with their more-the-merrier view of the gene pool. Every breach of celibacy should have been punished after the danger had passed, yet still the Jesuits insisted on adding to the population. Some of them had sought to modify and even abolish celibacy, but they had lost the fight. Corruption, corruption, he cried within himself. Three centuries of papal rule had committed and then practiced error, he told himself, clinging to the fact of his daughter’s existence and wondering if God was on the side of the burrowing heretics who sought to overthrow religious rule. The Church was no longer the Church. The City of God had died with Earth, and he was an impostor…

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time Stranger Suns

Stranger Suns Black Pockets

Black Pockets Brute Orbits

Brute Orbits Cave of Stars (Macrolife Book 2)

Cave of Stars (Macrolife Book 2) Macrolife

Macrolife Empties

Empties Heart Of The Sun Star Trek 83

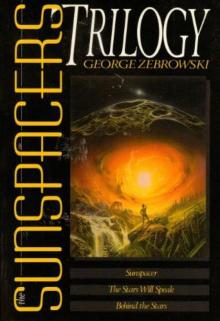

Heart Of The Sun Star Trek 83 The Sunspacers Trilogy

The Sunspacers Trilogy