- Home

- George Zebrowski

Macrolife

Macrolife Read online

Macrolife

A Mobile Utopia

George Zebrowski

Praise for MACROLIFE

“It’s been years since I was so impressed. Macrolife manages an extraordinary balance between the personal and cosmic elements. Altogether a worthy successor to Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker….

“I’m confident that George’s book is so good it doesn’t need any recommendation from me. You can quote that!

“One of the few books I intend to read again.”

—Arthur C. Clarke

“A work of sweeping imagination, exploring the fascinating implications of humanity’s breakout to the era of space colonies. Zebrowski addresses the deepest of questions: what is the human destiny? I read this book with great enjoyment.”

—Gerard K. O’Neill

“The first writer since Stapledon to get the Stapledonian flavor-vistas, perspectives, a kind of distant, serene motion. I think it’s a book that will last, if only for its first statement of an emerging, probably inevitable vision. The novel oscillates nicely between long view and close focus, capturing a mood and feeling that few even attempt in this field, and at the conclusion there is a genuine vast perspective evoked. The prose is very good—smooth, evocative, adroit—a solid work that will have a following of the best sort.”

—Gregory Benford

“Macrolife has acquired a cult following.”

—Stephen Baxter, Vector

“It is a very impressive book, not only because it is so well written but, most especially, because of its imaginative scope. It takes courage, confidence, and real ability to tackle these magnificent Stapledonian expanses of space and time, to confront the Universe in all its ever-changing majesty, and to dream of the infinite variety in which it can challenge man and change him (or make him change himself).

“That, of course, is the challenge of the science fiction field, and at a time when too much SF is trying to reduce the vastness and wonders among which we and our world live to mere backdrops for teenage suspense plots, it is refreshing and encouraging to have someone tackle the greater scheme and do it so splendidly. I hope there will be more books where Macrolife came from.”

—Reginald Bretnor

“Macrolife is the sort of novel that is not often seen in science fiction. It is thoughtful and deeply textured, somewhat reminiscent of Le Guin but on a much larger canvas; its scope alone should fascinate many readers, though its underlying philosophy is equally attractive.”

—Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

“With the publication of Macrolife, George Zebrowski takes his place next to H. G. Wells, Olaf Stapledon, and Arthur C. Clarke as a novelist of ideas on a cosmic scale. It is one of the most intellectually adventurous science fiction novels of all time.

“I am especially moved by Zebrowski’s success in striking a balance between the demands of thought and art…a splendidly wrought novel…much more than a book about space colonies, it presents a comprehensive vision of human destiny. Macrolife is magnificent.”

—W. Warren Wagar

“Macrolife is a thoughtful and detailed extrapolation of a staggering concept: the survival of our species in extraplanetary habitats. In rich, meticulous prose Zebrowski examines the emotional and philosophical ramifications of this concept, and in the novel’s powerful finale—the section entitled ‘The Dream of Time’—he creates a farsighted and poetic coda that is absolutely lovely. An important book.”

—Michael Bishop

“The first writer since Stapledon to get the Stapledonian flavor-vistas, perspectives, a kind of distant, serene motion. I think it’s a book that will last, if only for its first statement of an emerging, probably inevitable vision. The novel oscillates nicely between long view and close focus, capturing a mood and feeling that few even attempt in this field, and at the conclusion there is a genuine vast perspective evoked. The prose is very good—smooth, evocative, adroit—a solid work that will have a following of the best sort.”

—Gregory Benford

“What Zebrowski has tried in Macrolife is beyond the abilities of most writers in the field. He has shown the sweep of time, and the future evolution of mankind. Indeed, he has shown the future of all living things, from microbes to sun systems. And this on a canvas which stretches from now to Forever.”

—Howard Waldrop

“George Zebrowski’s ambitious novel Macrolife is constructed on a scale completely different from that of most science fiction being written today, so much of which is too conservative in its outlook. Macrolife—with its graphs, charts, illustrations, and interludes of theory—is as striking in form as it is imaginative in content. The book is in the best Utopian tradition of Wells and Stapledon.”

—Curtis C. Smith

“Impressive…Macrolife theme beautifully and convincingly developed: all based on credible cosmic technology. A history of eternity, done with grace and optimism. The last section, ‘The Dream of Time,’ with its serial universes and macrolives, has melodies and cadences reminiscent of Elizabethan sonnets. For contrapuntal contrast, the destruction of Earth is the best I ever read. It should satisfy even John, writing on Patmos. This, we agree, is the Way of Last Things.”

—Charles L. Harness

“Its sheer sweep, its grandeur of concept, its daring, integrity, and rational intelligence put to shame those science fictioneers who can only fill up the next hundred billion years with space wars and other high jinks orchestrated by heroes who are only giant dwarfs, fantasy projections of our as-yet rather primitive selves.

“Integrity, yes, and honesty. Here is a piece of fiction which may well be more than fiction, which demanded to be written, and to be written in its own terms. Macrolife is a work of grandeur and intelligence. With it, George Zebrowski’s career as mature prophetic writer really commenced….”

—Ian Watson

“The Utimate Utopia. There’s a lot of wonder in this book.’

—Richard E. Geis, Science Fiction Review

“A truly sui generis book…a massive intellectual achievement, a work that will be discussed and debated for years.”

—Thomas N. Scortia

“No higher praise could be offered than to say that Macrolife is almost Stapledonian in its approach to the subject of man in the galaxy.”

—Brian W. Aldiss, Trillion Year Spree

“A very plausible cosmology…Zebrowski has plotted and executed a fascinating story…superlative ‘hard science fiction.’…”

—United Press International

“An intellectual tour de force of great imagination and reverence for mankind’s potential.”

—Dean Ing

“Reminiscent of Stapledon’s future history in its breathtaking scope, and Blish’s Cities in Flight tetralogy in its grand theme.”

—Publishers Weekly

“…the gradual evolution of human society in the artificial worlds develops richly. The novel will probably be remembered rather longer than swifter, more superficial works.”

—Science Fiction & Fantasy Book Review

To Pam

for the beginning,

for the years after,

for the friendship and love,

these words

INTRODUCTION TO THE NEW EDITION

Increasingly, and sadly, American science fiction continues to be dominated by what George Zebrowski has referred to as “print television”: by books conceived and written as if they are TV films rather than works that challenge and enhance the emotions and the intellect of the reader, examples of “the precious life-blood of a master spirit, embalmed and treasured up on purpose to a life beyond life.”

George Zebrowski’s Macrolife is the latter kind of book, and that definition of a good book is almost three hund

red and fifty years old. It comes from the pen of the poet John Milton, in his long political pamphlet Areopagitca, which is also one of the masterpieces of English prose. Subtitled A Speech for the Liberty of Unlicensed Printing, this pamphlet of the year 1644 attacked state censorship, which was implemented by requiring official approval for the products of a printing press.

Nowadays works of science fiction—a literature of such potential to liberate the imagination and the mind—are censored commercially by a virtual conspiracy of publishers, editors, voters for prestigious awards, and, alas, by authors themselves. In many respects the pressures of commercial censorship are far worse than anything against which the author of Paradise Lost protested, because today’s pressures train readers to think and to respond shallowly, to consume the intellectual equivalent of fast food while convinced that they are feasting on fine cuisine. Which average reader nowadays—the audience for Milton’s polemic in his day—would get far beyond the title of that eloquent, finely wrought pamphlet? Even the title seems a bit of a mouthful.

George Zebrowski’s Macrolife certainly isn’t fast food.

“Print television” doesn’t simply refer to the flood of zippy, slick adventure fiction on the book racks, clones of previous SF, clones of Star Wars, clones of clones. The phenomenon is more insidious than that. For adventure fiction merely represents the low-level consensus of escapist entertainment. There also exists a high-level consensus consisting of literary work that is finely crafted, replete with a care for words and narrative tone and interactive dialogue that is both snappy yet unvulgar, populated with properly rounded characters, equipped with significant themes, laced with emotional concern, and with tasteful daring, and with a banner-waving show of insight and responsibility. Much of this work is also a sham, a confection. Too many budding writers write in order to see a well-wrought book in print with their name upon it, rather than to affect the consciousness of readers and even to change their lives in some minor or even major way (which, to me at least, is a principal reason for writing). Pretty soon those writers who do succeed become authorities on writing SF.

“Show but don’t tell,” aspiring authors are advised. Learn how to sugar the pill until the pill is buried deep, lost in a cyst of saccharine. Endless workshops-—which are commercial as much as literary since they are guiding the evolution of new authors toward survival and success in the consensus marketplace—and “How to Do It” articles by professional authors who have adapted to this ecological niche advise the young hopefuls how to cast narrative hooks like an angler fooling the fish and the best way to slip exposition of ideas painlessly into a tale without clunky chunks of facts or ideas interrupting the smooth momentum of the story. A major crime is to let one’s grasp on the reader slip for a moment or to hold up the onward rush of events. Thou shalt not discomfort the readers by making them slow down in the reading and actually think. They must simply experience the cunning, superficial semblance of deep feeling and intellection. Thus readers are conditioned not to think, so that ultimately they will not be readers of fiction but viewers. Thus writers are trained to think carefully about avoiding the appearance of rigorous thought.

George Zebrowski is an author who will make the reader think; and the ideas, the experience of his work, will not, therefore, slip away afterward like some phantom of thought, some illusion that the “viewing” of some subsequent book will presently eclipse.

This is why Arthur C. Clarke described Macrolife as “one of the few books I intend to read again,” adding that “it’s been years since I was so impressed. Macrolife manages an extraordinary balance between the personal and the cosmic elements. Altogether a worthy successor to Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker.”

Spurred on by peer fame in the form of Nebula and Hugo nominations and inclusion in “Best of the Year” anthologies as well as by inflated advances for “long awaited” first novels or sequels to previous, much-loved confections, the concept of the award-worthy piece of fiction—one which possesses the magic ingredients of balance, artistry, characterization, significance, et cetera—exists as a kind of abstract idol that now tends to condition, even if unconsciously, the kind of stories and novels that authors will write and how they will go about writing these. This system trains writers not to attempt other things or even to believe that those other ways could be valid. And editors punish deviancy as being “uncommercial,” which is tragic for authors, for readers, and for science fiction itself insofar as American science fiction commercially dominates world markets. To many people in America, consensus science fiction seems the only conceivable kind.

Thank God, then, for George Zebrowski.

Or should we, perversely, thank that madman Hitler? For Zebrowski, child of displaced Polish slave-workers, only came to America courtesy of the Nazi cataclysm, bringing with him a European tradition of literature, philosophy, and science that distinguishes him from most of his peers. He himself has commented that “Platonic dialogue, the symphonies of Mahler, Utopian fiction and Wellsian prophecy…these are the personal and technical sources of Macrolife.” Brian Stableford, reviewing Macrolife on its first appearance, was moved to wonder what possible future there could be in the science fiction field for a writer like Zebrowski. Macrolife was far more worthy “than a dozen sickly novels of the species that currently dominate the American SF scene,” yet the book seemed to Stableford to be a literary mule, something that just ought not to have been a novel. How deeply the divide has grown between fiction and nonfiction—even though historically this schism is of fairly recent origin and was irrelevant, as Stableford points out, to “the most ambitious works of the seventeenth century.”

Macrolifeis certainly an ambitious book, if any book is, yet though it is rooted in an older tradition of passionate thought, its own ambitions aren’t those of the past at all. They are of the future, of the furthest futures conceivable.

If any book is a treasure in Milton’s sense, here indeed is one, in a world where so many lcontemporary “masterpieces” are like doughnuts, fresh sugary hot sellers today, stale and discarded by tomorrow. The first edition of Macrolife nonplussed several reviewers, but favorable opinion has prevailed, for instance, in most major critical reference works and in Library Journal’s must-read list. Macrolife is one of Easton Press’s Masterpieces of Science Fiction.

In Stableford’s view there is simply no way that a vision such as Zebrowski’s can be presented using the narrative techniques of the novel, since—to take a couple of examples—these compel Zebrowski to have his characters lecture one another or require the protagonist to read a book of commentary “in order that we can read it over his shoulder.” For the novel has become preoccupied with character and narrative whereas Zebrowski is concerned with future sociology.

Isn’t it curious that one of the great classics of the twentieth century was George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four in which O’Brien lectures Winston Smith at length and in which Smith reads page after page of The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism, quotations from which occupy almost exactly one-tenth of the whole novel?

Yet Stableford’s criticism is correct, if reformulated to express precisely what is wrong with much American SF, namely, its betrayal of its own content in favor of novelistic tricks. Time and again, philosophical problems—of sociology, cosmology, the nature of existence, all of which are of the essence of science fiction—are presented but then hastily sublimated into mere story. One opens so many SF novels with such high hopes only to find that the science—in the broadest sense, of knowledge—is the merest pretext for a fictional adventure.

Zebrowski, for his part, has diagnosed a fundamental anti-intellectualism in American SF. In his view too many of its authors believe that they are sages, full of wise opinions, whereas the truth is that they have never thought rigorously enough as part of their basic existence.

On the contrary, they have schooled themselves to conjure up a mirage, an illusion of intellectual rigor. Zebrowski himself studie

d philosophy at the State University of New York and might have become an academic philosopher. The best teacher in that college (in his opinion), one Robert Neidorf, was a philosopher of science, but also a science fiction reader. The two strands could combine. “There should be more people,” Zebrowski has stated, “who are moved by the ideals and examples of science, and who understand its sociology and history, its importance to human aspirations and survival. Most workaday scientists rarely think about these things either.”

Its importance to survival. To a life beyond life, to quote Milton again. Survival, the triumph over powerlessness, and life beyond life are indeed the themes of Macrolife. Just as the writings of its character Richard Bulero are harked back to by subsequent characters, as rational visions of the future of life in the cosmos, so, too, may this novel of Zebrowski’s be harked back to aboard some space habitation out among the stars in the year 3000 as one of the founding texts, when other SF authors of today are as much remembered as medieval French court poets. If the future does follow a certain path, away from planetary surfaces into free space—as Zebrowski argues with a fierce conviction that it must—then he may well be regarded as a true literary seer. Few other writers are in the running for this sort of reputation.

Macrolife is a major vision of social intelligence transforming the cosmos. It is in three sections. The first focuses upon events in the year 2021 when the disintegration of the “miracle” all-purpose building material Bulerite destroys civilization on Earth. The events that are set in motion propel the first kernel of macrolife free of the solar system. The second and longest section deals with more mature macrolife of the year 3000. The star-faring habitat visits a degraded dirtworld to obtain raw materials with which to reproduce itself, then it returns with its new twin to Earthspace, where the first contact with alien macrolife occurs. The human race is accepted into the cosmic circle because people have learned how to link with artificial intelligence, thus overcoming—or at least taming—the instinctive passions inherited from dirtworld evolution. The final section begins a hundred billion years later when macrolife has filled the universe but the universe is beginning to wind down back toward the point of final collapse.

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time Stranger Suns

Stranger Suns Black Pockets

Black Pockets Brute Orbits

Brute Orbits Cave of Stars (Macrolife Book 2)

Cave of Stars (Macrolife Book 2) Macrolife

Macrolife Empties

Empties Heart Of The Sun Star Trek 83

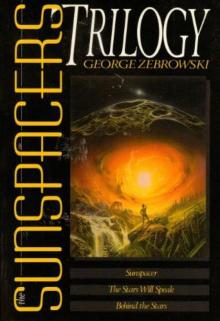

Heart Of The Sun Star Trek 83 The Sunspacers Trilogy

The Sunspacers Trilogy