- Home

- George Zebrowski

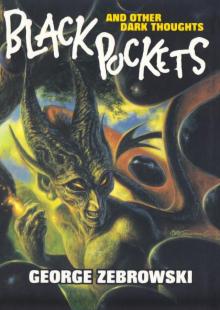

Black Pockets

Black Pockets Read online

EARLY BIRD BOOKS

FRESH EBOOK DEALS, DELIVERED DAILY

LOVE TO READ?

LOVE GREAT SALES?

GET FANTASTIC DEALS ON BESTSELLING EBOOKS

DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX EVERY DAY!

The Galaxy’s Greatest Newsletter

Delivered to Your Inbox

Get awesome tales of fantasy and science fiction once a week.

Visit us at www.theportalist.com

The Web’s Creepiest Newsletter

Delivered to Your Inbox

Get chilling stories of

true crime, mystery, horror,

and the paranormal,

twice a week.

Black Pockets:

And Other Dark Thoughts

George Zebrowski

For Pam dearest, who brightens my darkness

Foreword

FOR THIRTY YEARS NOW, HE’S BEEN AN enthusiastic voice on the phone, a bunch of nice letters, and the occasional check, in his fairly frequent guise as editor. Surprisingly, in all that time, we have never managed to meet face-to-face, like real normal people. Which is truly a shame.

When I introduced his SF collection The Monadic Universe twenty years ago, I tried to convince readers George was a funny (at times, bitterly so) writer who went straight back to the Aristophanic roots (though on a somewhat more cosmic stage).

“Zebrowski?” people would say. “Isn’t he the guy who writes galaxy-spanning sagas—”

“—of Stapledonian magnitude?” I would complete their question. “Yes,” I would then say, “but like me, he also thinks that just because it’s serious doesn’t mean it has to be long, dull, boring, and humorless.”

“Really?” they would say. “I thought it had to be.”

What you hold in your hands is George Zebrowski’s first collection of horror stories, culled from throughout his career, with an emphasis on the more recent things, and one brand-new-writtenjust-last-Thursday (well, all the last Thursdays from the past two years) novella, the titular “Black Pockets.”

What George has done, sitting there in Upstate New York, a place as unknown to me as the Great Rill Valley on Mars, is to divide these stories into Personal, Political, and Metaphysical horrors, i.e.: stories that should scare you individually, stories that should terrify you as a social animal, and stories that should scare the whole goddamn human race, in the collective.

Part of the—if we may so speak—beauty of this book is that George can write about people who are not like him (or you, or me). Many are not as intelligent, nice, thoughtful, or as sensitive as their author. (Writing about morons is easy—limited vocabulary, concrete nouns, declarative partial sentences, no conceptualization —although Faulkner and Steinbeck were way ahead of everybody else—and writing about geniuses is easier than you think—abstract modifiers, conceptualization, complex sentence structures—although here, too, Bester (in “The Pi Man”), Daniel Keyes, and Don De Lillo did it better than anyone else). What is really hard is writing about someone just a little less, or a little more intelligent, sensitive, caring etc. than you (and most people) are. Zebrowski pulls this off many times in these stories. One of the most chilling, “The Wish in the Fear,” is so good at what it does that you forget what the story is about until the next-to-last line, and then you remember, with a vengeance. (This is also one of those stories that is going to finish after you’re read the last line—he’s made it so you finish the story after he’s through. I guarantee it.) A couple of the earlier stories in here needed a little more room to breathe—good though they are—but not this one.

His deft use of character is such that (even reading them in this collection) you forget that most horror stories just fill time before the protag is eaten or impaled or gets their comeuppance somehow. That’s other writers.

Not in these. George has set himself the writerly goal of having the horror come out of the situations and character flaws of his people, not from some ancient evil trespassed, or Cthulvian terror, nor now what has become that cliché —the serial killer. (What did non-supernatural horror writers do before Ed Gein was caught?)

What I’m going to propose here is that George Zebrowski is writing a new kind of dark fantasy story—as new as, say, Fritz Leiber’s “Smoke Ghost” was in its time—the kind that led to Unknown Worlds (1939–1943). Especially in the stories he puts into the Political Horrors and Metaphysical Fears sections.

There has never been a zombie story like “I Walked With Fidel”—true not only to a dead Cold-War world that has passed with its polarized ideologies (as surely as that passed Colonial World—which led to voodoo—has gone from this earth): the story manages to be true to both post-Superpowers times and to Castro, whose ideals were as betrayed by the nature of revolutions and the Soviet Union as by the warmongering antagonism of the United States. Read it and say it ain’t so, José.

George is not afraid of the Big Frightening Ideas either. The two newer centerpieces of the collection, “Black Pockets” and “A Piano Full of Dead Spiders” deal with truly existential problems, like in the latter—if you’re a composer, and your tunes come from spiders playing them in your piano, what happens when they die? Are there spiders in your piano? In the first place? Which died first, the spiders or your talent? Is there redemption in this cold world?

In “Black Pockets,” the questions keep coming: you’re given a great, heretofore unknown power by the nemesis of your existence as he is dying; for he has some unfinished business he needs done before you can use the power for revenge yourself. The protag finds, like Wells’s Invisible Man, that power, in and of itself, instead of avenging the Great Wrongs of Your Life, becomes a convenience, and otherwise innocent bystanders (wrong time, wrong place) get it used on them. At the core of the story is the truly frightening question: at what point does revenge become so all-consuming it clouds your judgment? Oh yeah? and how do you know?

Be warned: this isn’t just another standard horror-trope collection (they never are, from Golden Gryphon). There’s only one old castle in the book. The settings range from the apartments next door to the hollowed-out asteroid worlds beyond the orbit of Pluto; the social strata from impoverished students to the people who live in the big houses on the hill in Yourtown USA.

I’ve had the privilege to read this collection hot-off-thecopier. You’ll have the joy of reading it in some beautifully designed package from the publishers. Whatever the format, whatever the circumstances under which you read it: It’s one powerful, varied, and wonderful batch of tales you have before you.

—Howard Waldrop

Vernal equinox 2005

Personal Terrors

are the first ones we know...

Jumper

“I GO TO SLEEP AND WAKE UP SOMEWHERE ELSE.”

She looked directly at him as she spoke, and it seemed clear that he was dealing with an unusually controlled personality. She wore an impeccably tailored tweed business suit, white blouse, blue tie, and black shoes. Her brown hair was professionally permed; her make-up was light, with almost no lipstick. He gazed at her without comment, hoping to catch a moment of weakness in her facade, but there was nothing.

“Well, Doctor, what do you think?”

He smiled. “Oh, I doubt very much that you’re traveling in any way. You’re already there, where you wake up, but you’ve dreamed that you started somewhere else. Naturally, it seems surprising to find yourself where you actually are.”

“That is not the case, Doctor,” she replied determinedly.

“Miss Melita, you’re simply mistaking where you go to bed, nothing more.”

She grimaced, as if she’d caught him at something. “You avoid calling me by my first name, or Ms. Melita. I once went to an idiot in your professi

on who insisted that I use his first name. Do I intimidate you, Doctor?”

“Not at all. I’m not hung up on the authority of formal address. Some of my colleagues like it. Others simply want the patient to feel informal and relaxed.”

“Yes, they call patients by first names but introduce themselves as Dr. so-and-so.”

“I’ll go by your preferences.”

She stared at him without blinking, and he knew that it would be Miss Melita and Dr. Cheney. An old-fashioned female who might need rescuing from herself. The immaturity of the thought startled him, and he realized that she was having a strong, unconscious effect on him.

He looked at her file on his desk. “I see that your physical checks out well, and you have no reported history of sleep disturbances.”

“Doctor, I have no memory of going to the places where I wake up. I waken there and have to come home. Yesterday I woke up in my ex-lover’s house. It was empty and for sale. I’m certain I was home when I fell asleep.”

“These kinds of things can be very convincing,” he said. “Were you wearing pajamas?”

“Of course not. I go to bed wearing clothes, just in case. I’ve jumped more than a dozen times in the past few months.”

“What do you think it is?” he asked in his best neutral tone.

“I don’t know. Movement from one place to another without covering the distance between,” she replied glibly.

“A kind of quantum leap?”

“What do you mean?”

“It’s a term from physics,” he said. Patients sometimes like to give, or hear rational-sounding explanations. Imaginative plausibility could be a sign of delusion.

“Who cares,” she said. “It happens. I know it does. The first few times were pretty embarrassing.” Her tone was insistent, but she kept her composure.

“What do you think it means?”

“I sometimes feel as if I’m searching for the right place to be,” she said, “but it keeps eluding me. I wake up in the wrong places.”

“Is there a right place?” he asked.

“I don’t know. I can’t think where it might be, but I feel strongly that it exists.”

“Doesn’t that give you a clue?” he asked, setting in motion his usual probing rigmarole.

“What could it tell me?”

“You may be hiding it from yourself,” he said.

“I’ve thought of that. It may be a place I only know about, but have never visited.”

“And you may not really want to go there, while at another level you do. Anyone can be of two minds, Miss Melita. I can see, whatever is going on, that this search is important to you. My job will be to keep you from deluding yourself.”

“You’re confident I’ll take you on,” she said.

“Shall we set up a schedule? I charge by the hour, five hours paid in advance.”

She looked at him with skepticism. “I know you’re expensive, Doctor. I’d like to set a deferred-payment plan.”

He smiled at the first hint of insecurity in her voice. “Ah, but payments are part of the treatment, Miss Melita. They sow an attitude of responsibility in your unconscious, making it a partner in your recovery. You’ll get better sooner.”

There was a blush in her pale cheeks, suggesting that she was responding to his authority, even accepting that she might have a problem.

She stood up, as if to leave. “What a crock, Doctor. I simply don’t want them to know at work that I’m seeing you, so I can’t use my medical coverage. I can start paying next month, when I can draw on my savings. Anyway, you don’t believe me.”

She was beautiful, he noticed, slim yet womanly, standing on low heels in a dancer’s graceful pose, her back slightly arched, toes out a little.

“Are you successful, Doctor?” she demanded.

“I’d like to think I am,” he replied calmly.

“How long do you sleep?”

“Oh, I’d say about eight hours.”

“Really successful people sleep less than five or six,” she said.

She begrudges herself sleep, he noted, drives herself and others hard. Her lapses of memory were not surprising.

“I’d say your business has leveled off,” she continued, “and may even be on the way down. You’re heavy into investments as a hedge against a practice that won’t grow. You’re doing well at them, but they have to be fed. You could go either way in the next few years.”

He leaned back and smiled, trying not to think of what tax reform had done to his portfolio, determined not to show her she’d hit home.

“We’re off the point, Miss Melita.”

She sat down and crossed her legs. “Yes, of course. My only interest is in your competence.”

Competitive chatter was a habit with her, he realized.

“I can prove to you that I jump,” she said, with a tremor in her voice.

“You’re welcome to try,” he said, “but only if I’m to be your doctor, and I’m not sure I want to take you on.”

She swallowed, and he watched the muscles working in her pale throat. “Doctor, I apologize for my remarks about your business and character.” She leaned forward slightly. “I don’t know why this is happening to me, Doctor, but you could easily check my story. I have videotapes of me disappearing from my bed.”

“Look,” he said firmly, “it’s just not possible for you to move yourself while you’re asleep, unless you get up and convey yourself there. I know you believe you’ve disappeared from one location and appeared in another, but, take my word for it, it’s not a true experience, not at all, never. Videotapes can be faked.”

“Okay, come home with me, lock me in my bedroom, and wait. When I call you from somewhere else the next morning you’ll know it’s true.”

He knew then that he should not take her case. Simple neurotics made the best patients; they asked for help with life’s problems and only thought they were sick. They could be made to feel helped. If this woman could imagine that she teleported from her bedroom every night, it would be nothing for her to imagine worse things. To go to her home at night would be asking for a sexual-harassment suit.

“I’ll pay you six months in advance,” she said, “next month.”

“Can you afford it?” he asked, wondering if in fact she wanted him to come on to her.

“No, I told you it’ll be my savings, but I must prove that what happens to me is real. Then I’ll need you to find out why it happens. Okay, I can’t be completely sure it happens unless someone like you documents it.”

He sighed, unable to decide.

“This could make your name, Doctor. You’ll witness a disorder that exhibits itself in a unique way. You’ll write about it, go on talk shows, bring in more patients. Hell, you might not need patients after that.”

He shook his head and smiled. “I shouldn’t take your money. What do you do, Miss Melita? Your entry on my form is vague.”

“I’m an executive at a telecommunications company.”

“Here in New York?”

“Yes. I’ve taken a leave of absence for six weeks.”

“Are you lesbian?” he asked.

“That’s not your business unless you take my case.”

He leaned forward. “Do you really want help, Miss Melita?”

She sat back in her chair, uncrossed her legs, and folded her hands in her lap. “Yes, I’m lesbian, but I’ve had male lovers. It never works out, even though I’m attracted to some men and try hard. Not because they find out, but for other reasons. I can’t be orgasmic with men. They’re too threatening.”

“Were you raised by both parents?”

“No, by my father. My mother died when I was small, just after we arrived in this country. My brother ran away when I was ten, and I’ve not seen him since.”

“Is your father living?”

“Yes,” she said softly.

“Okay, I’ll take you on,” he said. Her story had made him curious. How could a person of her obvious intellig

ence and good sense, who gave no sign of illness, tell such a flaky tale? “Make an appointment,” he added, “for the day after you’ve had this experience of yours again.”

“You don’t want to check my story?” she asked.

“Not by sitting up all night at your place,” he said, imagining the softness of her skin under her blouse.

“It’s the only sure way to find out.”

“Miss Melita, I’d have to ask a colleague to come with me, or hire a nurse of unquestioned integrity to serve as a witness. Maybe I’d need them both to prove that my presence was purely professional.”

She bit her lower lip. “Oh, I see. But you already know I wouldn’t be interested in you, Doctor.”

“Do call and make an appointment, Miss Melita.”

As she got up and left, he realized that there would be no more to it. She’d see him a few times and then stop coming. He felt a bit lost and disappointed for the rest of the day.

When she arrived for her first appointment on the following Monday, dressed in jogging clothes, his insides leaped with naive joy at the sight of her. Gone was the executive bitch facade. The big kid who showed up in her place was much more appealing and clearly in need of his help.

“Oh, the clothes,” she said, noticing his stare. “I slept in them, so I could get home.”

He looked down at his desk to hide his sudden rush of attraction for her. Her change from cool executive to willowy athlete both excited and annoyed him; he had never become this vulnerable with a patient.

“There’s been a change,” she said, dropping into the chair.

“What kind of change?” he asked uneasily.

“I was dreaming about dying before I woke up in a park somewhere in Brooklyn.”

“A park?” he asked stupidly, watching her lips and the movement of her neck muscles. Her sweaty youthfulness was overpowering.

“I think it was a park. It was still dark when I left, so I wasn’t paying much attention. Doctor, I think I’m going to die.” She looked directly at him. The dismay in her eyes was crushing, but in a perverse way it only made her more beautiful.

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time Stranger Suns

Stranger Suns Black Pockets

Black Pockets Brute Orbits

Brute Orbits Cave of Stars (Macrolife Book 2)

Cave of Stars (Macrolife Book 2) Macrolife

Macrolife Empties

Empties Heart Of The Sun Star Trek 83

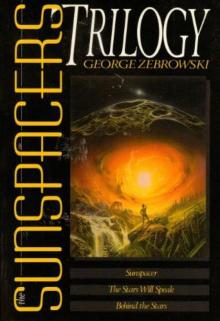

Heart Of The Sun Star Trek 83 The Sunspacers Trilogy

The Sunspacers Trilogy