- Home

- George Zebrowski

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time Read online

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time

George Zebrowski

To W. Warren Wagar,

Hero of my youth,

Friend of my middle age,

Who helped me think.

Introduction

Stories and novels are an author’s mindchildren. They grow slowly, and you write every line of their DNA yourself! Whatever is wrong stays wrong, but what inspired you to write them also remains. As with biological progeny, there are elements that are beyond your control, and it is that unpredictable creativity that will make them interesting to read.

A short story is a lonely voice, not easily heard these days, and certainly not the most important thing that goes on in the world. It brings to the reader a brief design and voices that strive to be heard within that brief design, much like the instruments in a string quartet. Read too quickly and you may miss the subtleties.

In addition to the voices of its characters, a science fiction story should also voice thoughts, and so requires a thoughtful reader; or at least one open to the seductions of thinking, to the beauties of an idea or a rounded bit of reasoning, as much as to the trills of emotion and the thrills of action. A science fiction story without thought must surely be a lesser science fiction story—or perhaps not a science fiction story at all.

These stories had this kind of reader, now and then, in the editors who published them and in the reviewers and readers who saw enough in the stories to comment on them. They were usually lone reactions (I rarely had more than one for each story), but they seemed to hear the inner voices within each story’s design and language.

Design, language, and the thoughts and emotions expressed by people. These are the ingredients of true science fiction stories, with thoughts being the distinctive characteristic, like musical structures balanced against the actions.

“The Water Sculptor” was my first published story. I took it with me to the first Clarion Writers Workshop in 1968. An editor at Charles Scribner’s Sons in New York later saw it in a proposed but never published collection of stories from that workshop, and invited me to lunch. He gave me my first contract for my novel, Macrolife (1979), which was published by Harper & Row after that editor left Scribner’s. Still, this was the story that called me to the attention of a major publisher, when it was still unpublished and a bit devalued in my mind by two rejections by major markets. I had also foolishly let my brother and his girlfriend read the story. “Who do you think you are?” she said. “Too serious to be published,” he said.

I remember dropping it off to the editor of a paperback anthology series on my way to my summer job with the New York City Parks Department. My brother was with me that day, on his way to the same summer job, and I knew from the looks he gave me that he was wondering what I could possibly expect from such behavior. I got a quick letter back from the editor asking for some revisions. I saw the virtues in the requests, did the revisions in about two hours the next day, and again delivered the story personally, alone, on my way to work. Another letter informed me that the editor liked the story, and I would hear by October whether the story was going to be included in the anthology. A check arrived well before October; and then one day, a few weeks before Christmas, as I was bringing home some laundry to my off-campus college apartment, I saw a package stuck in my mailbox.

I dropped my laundry on the porch, reached for the package, opened it clumsily—and there it was! Infinity One, a paperback anthology. I turned to the contents page and there was my name by the story. I simply stood there, trying to absorb the fact that I had done it.

I immediately took the story over to the hospital, where Pamela Sargent, my lifelong companion, was in for some repairs.

“What’s this?” she asked, looking pale and tired but beautiful with her long dark hair strewn prettily over the pillow.

“Take a look,” I said.

She looked and said, “Oh, a collection. Thanks.”

“Look closer,” I said, “—at the contents page.”

She looked, and the puzzled expression on her face changed to a smile—and that moment on the porch with all my laundry repeated itself in a much better way.

“I’ll leave the collection with you,” I said.

“Aw—okay,” she said, and I wondered whether she was looking at me differently.

Nearly a hundred stories later, there has been nothing like that doubled moment, although there have been moments. A writer has only a limited number of “firsts” in his working life, so don’t let them pass by too quickly. Remember how little it took to be happy with one story. In all fairness to my brother’s girlfriend, she spoke to me decades later, and said, “Who knew!”

The story received praise and a Nebula recommendation from James Tiptree, Jr., and from Jerry Pournelle—two very different writers. The story certainly owes to the work of Arthur C. Clarke. It also presents the problem of orbital space junk, which continues to get worse.

I returned to Christian Praeger’s adventures in “Parks of Rest and Culture” and in “Assassins of Air,” to find out how he crossed paths with the “water sculptor.”

“Heathen God” was my fourth published story. Barry Malzberg’s “author’s workout” series of springboards and sketches for writers in the SFWA Bulletin provided the impetus. I added quite a bit to this sketch, but Barry’s spirit was somehow holding my hand all the way. The story was partly written in my head during my summer job for the New York City Parks Department, and “remembered” onto paper scene by scene whenever I had the chance. It was a Nebula Award finalist and was included in Nebula Awards Seven (Harper & Row, 1972), and is my most reprinted and translated story. I went to the awards banquet in New York City, happy to be a nominee, knowing that I was not getting first place. Friends of mine attended: also my mother, to see what I was doing with my life; my brother, who ducked out early, just after I introduced him to Lester del Rey, an author he had read. I introduced my mother to Isaac Asimov, who hugged her; to James Gunn, who thanked her for producing me; and to Harlan Ellison, who was nonplussed—probably because my mother always looked and acted like a cross between Marilyn Monroe (the blonde look) and Zsa Zsa Gabor (the European accent).

“The Soft Terrible Music” I wrote for John DeChancie’s and Martin Greenberg’s collection Castle Fantastic because I was in love with two things at the time: the “warm” valley in Antarctica, where I thought it would be nice to have a house; and the idea of a spatially extended house—an idea that goes back to Robert A. Heinlein’s wonderful 1940 story, “And He Built a Crooked House.” Themes of love and revenge crept into my story. Expensive houses in protected and exotic places often have great crimes associated with them. John DeChancie wrote me an enthusiastic reaction to the story, in which he described the story as being of “the true quill.”

“The Sea of Evening” proposes an answer to Fermi’s Paradox, which asks: if the universe is full of intelligent life, then where are they? Why haven’t we been contacted? My story, which also owes a bit to Arthur C. Clarke’s “The Nine Billion Names of God” in its technique, gives one answer to Enrico Fermi. Konstantin Tsiolkovsky asked the same question many years before Fermi, and also gave an intriguing answer. I tend to think there may be several answers to the question, rather than one.

Poul Anderson created a world named Cleopatra out of basic astronomical and physical possibilities, as an imaginary planet circling a distant star. He then wrote a long story set there, and a number of new writers added stories and lore for the collection, each playing with Anderson’s carefully wrought backdrop. I took the opportunity to have this world’s

existence intersect with my own Macrolife mosaic of stories and novels about mobile, self-reproducing habitats. Poul, who had also done some background work for me in part one of Macrolife, was delighted, and even suggested that I might make a larger work from “Wayside World.”

“In the Distance, and Ahead in Time” is more directly in the Macrolife mosaic; the people of the mobile habitat arrive at the beginning of the story rather than at its end, and cause all sorts of ethical/political problems, not to mention personal difficulties for my characters. Yet the issues of land expropriation are very much still with us, beginning with just about every human migration of history, to the violent seizure and settling of North America, to the Middle East. I wrote this story for my friend Chad Oliver, whose anthropological science fiction remains without peer.

Contrary to fashionable amnesia, the idea of virtual reality is far from new. It fades into modern science fiction from the 19th and 20th centuries, through such books as Peter Ibbetson (1891) by George Du Maurier, Laurence Manning’s 1933 story, “The City of Sleep,” James Gunn’s The Joy Makers (1961), Daniel Galouye’s brilliant Counterfeit World (1964), and many others. The wish takes on practical reality through today’s computer engineering human interface ideas. “Transfigured Night” was how I was getting there with this theme. “Between the Winds” takes the theme to one ultimate result, as humanity voyages into sea changes.

Ten stories.

Ten dreamtimes out of my life, when I was happy to write them down.

—George Zebrowski

Spring 2002

Near Futures

The Water Sculptor

Sitting there, watching the Earth below him from the panel of Station Six, Christian Praeger suddenly felt embarrassed by the planet’s beauty. For the last eight hours he had watched the great storm develop in the Pacific, and he had wanted to share the view with someone, tell someone how beautiful he thought it was. He had told it to himself now for the fiftieth time.

The storm was a physical evil, a spinning hell that might reach the Asian mainland and kill thousands of starving billions. They would get a warning, for all the good that would do. Since the turn of the century there had been dozens of such storms, developing in places way off from the traditional storm cradles.

He looked at the delicate pinwheel. It was a part of the planet’s ecology—whatever state that was in now. The arms of the storm reminded him of the theory which held the galaxy to be a kind of organized storm system which sucked in gas and dust at its center and sent it all out into the vast arms to condense into stars. And the stars were stormy laboratories building the stuff of the universe in the direction of huge molecules, from the inanimate and crystalline to the living and conscious. In the slowness of time it all looked stable, Praeger thought, but almost certainly all storms run down and die.

He looked at the clock above the center screen. There were six clocks around the watch room, one above each screen. The clock on the ceiling gave station time. His watch would be over in half an hour.

He looked at the sun screen. There all the dangerous rays were filtered out. He turned up the electronic magnification and for a long time watched the prominences flare up and die. He looked at the cancerous sunspots. The sight was hypnotic and frightening no matter how many times he had seen it. He put his hand out to the computer panel and punched in the routine information. Then he looked at the spectroscopic screens, small rectangles beneath the Earth watch monitors. He checked the time, and set the automatic release for the ozone scatter-cannisters to be dropped into the atmosphere. A few minutes later he watched them drop away from the station, following their fall until they broke in the upper atmosphere, releasing the precious ozone that would protect Earth’s masses from the sun’s deadly radiation. Early in the twentieth century a good deal of the natural ozone layer in the upper atmosphere had been stripped away as a result of atomic testing and the use of aerosol sprays, resulting in much genetic damage in the late eighties and nineties. But soon now the ozone layer would be back up to snuff.

When his watch ended ten minutes later, Praeger was glad to get away from the visual barrage of the screens. He made his way into one of the jutting spokes of the station where his sleep cubicle was located. Here it was a comfortable half-g all the time. He settled himself into his bunk, and pushed the music button at his side, leaving his small observation and com screen on the ceiling turned off. Gradually the music filled the room and he closed his eyes. Mahler’s weary song of Earth’s misery enveloped his consciousness with pity and weariness, and love. Before he fell asleep he wished he might feel the Earth’s atmosphere the way he felt his own skin.

I wish I could hear and feel the motion of gas molecules in the upper air, the whisperings of subtle energy transfers …

In the Pacific, weather control engineers guided the great storm into an electrostatic basket. The storm would provide usable power for the rest of its natural life.

Praeger awoke a quarter of an hour before his watch was due to begin. He thought of his recent vacation Earthside, remembering the glowing volcano he had seen in Italy, and how strange the silver shield of the Moon had looked through Earth’s atmosphere. He remembered watching his own station six, his post in life, moving slowly across the sky; remembered one of the inner stations as it passed Julian’s station 233, one of the few private satellites, synchronous, fixed for all time over one point on the Earth. He should be able to talk to Julian soon, during his next off period. Even though Julian was an artist and a recluse, a water sculptor as he called himself, Julian and he were very much alike. At times he felt they were each other’s conscience, two ex-spacemen in continual retreat from their home world. It was much more beautiful, and bearable from out here. In all this silence he sometimes thought he could hear the universe breathing. It was alive, the whole starry cosmos throbbing.

If I could tear a hole in its body, it would bleed and cry out for a bandage …

He remembered the stifling milieu of Rome’s streets: the great screens which went dead during his vacation, blinding the city, the crowds waiting on the stainless steel squares for the music to resume over the giant audios. They could not work without it. The music pounded its monotonous bass beat: the sound of some imprisoned beast beneath the city. The cab that waited for him was a welcome sight: an instrument for fleeing.

In the shuttle craft that brought him back to station six he read the little quotation printed on the back of every seat for the ten thousandth time; it told him that the shuttle dated back to the building of the giant Earth station system.

“… What we are building now is the nervous system of mankind … the communications network of which the satellites will be the nodal points. They will enable the consciousness of our grandchildren to flicker like lightning back and forth across the face of the planet …”

Praeger got up from his bunk and made his way back to the watch room. He was glad now to get away from his own thoughts and return to the visual stimulation of the watch screens. Soon he would be talking to Julian again; they would share each other’s friendship in the universe of the spoken word as they shared a silent past every time they looked at each other across the void.

Julian’s large green eyes reminded him each time of the view out by Neptune, the awesome size of the sea green giant, the ship outlined against it, and the fuel tank near it blossoming into a red rose, silently; the first ship had been torn in half. Julian had been in space, coming over to Praeger’s command ship when it happened, to pick up a spare part for the radio-telescope. They blamed Julian because they had to blame someone. After all, he had been in command. Chances were that something had already gone wrong, and that nothing could have stopped it. Only one man had been lost.

Julian and Praeger were barred from taking any more missions, unfairly, they thought. There were none coming up that either of them would have been interested in anyway, but at the time they put up a fight.

Some fool official said publicly that they were unfit to represent mankind beyond the solar system—a silly thing to say, especially when the UN had just put a ban on extra-solar activities. They were threatened with dishonorable discharges, but they were also world heroes; the publicity would have been embarrassing.

Julian believed that most of mankind was unfit for just about everything. With his small fortune and the backing of patrons he built his bubble station, number 233 in the registry; his occupation now was “sculptor,” and the tax people came to talk to him every year. To Julian Earth was a mudball, where ten per cent of the people lived off the labor of the other ninety percent. Oh, the brave ones shine, he told Praeger once, but the initiative that should have taken men to the stars had been ripped out of men’s hearts. The whole star system was rotting, overblown with grasping things living in their own wastes. The promise of ancient myths, three thousand years old, had not been fulfilled …

In the watch room Praeger watched the delicate clouds which enveloped the Earth. He could feel the silence, and the slowness of the changing patterns was reassuring. Given time and left alone, the air would clean itself of all man-made wastes, the rivers would run clear again, and the oceans would regain their abundance of living things.

When his watch was over he did not wait for his relief to come. He didn’t like the man. The feeling was mutual and by leaving early they could each avoid the other as much as was possible. Praeger went directly to his cubicle, lay down on his bunk, and opened the channel, both audio and visual, on the ceiling com and observation screen.

Julian’s face came on promptly on the hour.

“EW-CX233 here,” Julian said.

“EW-CXOO6,” Praeger said. Julian looked his usual pale self, green eyes with the look of other times still in them. “Hello, Julian. What have you been doing?”

“There was a reporter here. I made a tape of the whole thing, if you can call it an interview. Want to hear it?”

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time Stranger Suns

Stranger Suns Black Pockets

Black Pockets Brute Orbits

Brute Orbits Cave of Stars (Macrolife Book 2)

Cave of Stars (Macrolife Book 2) Macrolife

Macrolife Empties

Empties Heart Of The Sun Star Trek 83

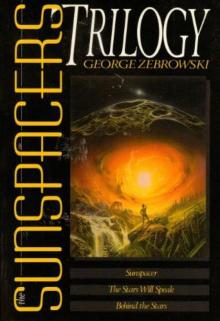

Heart Of The Sun Star Trek 83 The Sunspacers Trilogy

The Sunspacers Trilogy