- Home

- George Zebrowski

Empties

Empties Read online

Empties

A Novel

George Zebrowski

For Fritz Leiber,

who taught me how to brew blood coffee

“Love your neighbor, but don’t pull down the fence.”

—Chinese Proverb

1

The morning sun burned in the old black man’s eyes as he sat on the bench by the East River, gripping his knees, a broken liquor bottle at his feet—as if the sunrise had frightened him to death, Benek thought, irritated at having been called out at dawn. There was dried blood in the grizzled wino’s ears, on his neck, and on the shoulders of his ragged tweed jacket. Benek looked for a head injury, but the thick, white hair, pasted down with sweat and dirt in the unseasonably hot morning, was undisturbed.

“Looky here, Detective,” said the wiry young cop on the beat, squatting by the iron fence. Benek went over and leaned down. Ragged bits of what seemed to be flesh were stuck to the sloppily painted black posts. “Looks like something got shoved through here,” the cop added.

“See if there’s anything below,” Benek said as they both straightened up. Being up at this hour recalled his teen years in Perth Amboy, when his father would come home drunk at dawn, yelling for him to get up for school, hours too early, then staggering down to pass out on the unmade bed in the basement room to which his wife had exiled him.

The hot sunlight made the city’s dust seem dirtier on summer mornings, but not in October. Benek peered down over the rail and coughed from the river’s stench, then turned and said to the cop, “Bag everything you can find for the lab, front and back photos of the body, closeups of the head, front and side.” More wasted time would not pay for his lost sleep, but the dead man might have approved.

The cop said with surprise, “For a wino?”

Benek said, “And ask around the neighborhood houses. Maybe someone saw what happened.” He wanted to at least look as if he was doing the evidence team’s work for them, and it might make their judgment call look bad if something turned up. But that would not be his fault. As a kid he had always stuck his finger in the coin return slot when passing a public phone, and been rewarded often enough to keep doing it. Detectives Third Class needed all their chances.

“Looks to me like he drank some bad stuff,” the young cop said.

Benek looked at the unshaven face. Mouth open, lower lip sagging, glassy eyes staring into the dawn glare. A fly landed on the nose, crawled down over the upper lip and crept onto the pissyellow teeth. What was it here that told a story? Any kind of story, or even a piece of one. Most likely there was no more to tell than what he could guess right here. A defeated man startled by his own end. Well, it got me, he seemed to be saying. It was my turn. Benek felt a twinge of compassion.

The young cop took out a fresh handkerchief and wiped the sweat from his face. “So what do you think?”

Benek grimaced, feeling sticky, and opened his raincoat. He was still wearing yesterday’s white shirt and underwear because he had slept in them. The slacks and blazer he had intended to drop off at the cleaner’s this morning. It had been unexpectedly warm when he’d left his apartment at 6:00 A.M. He had noticed too late to go back upstairs to leave his raincoat. Without a shower he’d get stickier as the day wore on, and he’d have to leave the coat at the station, and might forget to take it home with him. “Check his clothes for any kind of ID,” he said, then headed for his car just as the morgue wagon rounded the corner, crept quietly by the row of expensive apartment buildings, and pulled up on the river walkway, where it sat like a mournful beast.

He stopped by his Volvo and considered knocking on a few of the shiny, brass-fitted doors to ask the questions himself, but decided against it. These taxpayers might complain, even though it was one of them who had called the police, probably annoyed by the sound of the bottle breaking when it had slipped out of the dying man’s hand, but he knew they would look at him strangely if he came asking questions. The look on their faces would be a question: what do you care?

He got into the car and sat back, resenting the loss of his remaining three hours of sleep, then turned and looked back at the man on the bench, where the youthful, almost angelic duty cop was going through his pockets, hurrying so that he wouldn’t further disturb the neighborhood by delaying the removal, getting a good start on his twenty-years-to-pension. It was a heart attack or massive stroke, Benek told himself. The old man might have felt it coming for some time, maybe even hoping that the bad liquor would hurry it along. He had died quickly, to get that freeze in his eyes. Benek wondered if the man had any living friends or family, feeling that there had to be something here to justify being called out so early. Of course, had to be was not the same as was, but any man’s death was a larger loss than the sleep of the living. It had to be, he told himself, or what are we?

The precinct was deserted when Benek came in at 7:30 A.M. Andy Rubelev, the night sergeant, was still at his desk above the rail, reading the Daily News, but it seemed to Benek that it had always been another paper. In the far left corner of the large room, at the table shoved up against the green wall that never got painted, Arty Levin, the yeshiva student, was doing his usual clerical work before school. He sat in his skullcap and clean blue suit, staring at the computer screen as if studying a Talmudic text, which operating the computer might just as well have been to the other members of the precinct who had convinced themselves that they were no longer the right age to learn. In the far right corner, three teenage boys sat in the holding tank, exhausted and nearly asleep from their night’s doings. Repeat visitors, Benek knew that he would see them again.

As he started up the iron stairs that snaked up from the center of the room to the second floor, he heard shouting behind him, turned, and looked back to see a tall, red-haired man come in cursing about what kind of city this was where your car got stolen an hour after you got here. He reminded Benek of Hadrian’s coin-profiles, the Roman general who had built a wall across Britain to keep out the barbarians. A short, blond guy came in after him, and they marched up to Rubelev, who rose and told them that he was going off shift but someone would be with them in a few minutes to take down their complaints. You gotta be kidding, the short blond guy said, and Benek pictured him as Caligula. Of course, no one really knew the color of Caligula’s hair, or Hadrian’s for that matter.

Turning away from the morning’s comedy act, Benek hurried up through the ceiling to the Detective Division on the second floor and made for the food cart in the hallway. Mercifully, the red light on the coffee machine was already on. He filled a large Styrofoam cup and went to his alcove at the end of the hall, hoping to catch up on his paperwork before the day’s horrors began calling in.

A black mood seized him as he sat down in his chair, and he pitied the stiff on the riverside bench. He stared at the blank screen of his computer terminal for a while, then sipped some coffee, but it was too hot. He put the cup down carefully on his desk.

At 8:01 his phone chirped. The switchboard was wasting no time. He picked up the old wired receiver and said, “Detective Benek. Name, please.”

“Uh—my name is Sammy Rebollo, and I’ve just been robbed,” the man said in a low grumbling voice, then gave his address, just six blocks from the precinct. “My groceries—I put them under the stairs in my lobby, then went to park. They were gone when I got back. Lobby’s locked, so it’s gotta be some bastard in the building.”

“Do you have any idea who that... might be, Mr. Rebollo?” Benek asked, wanting to say that he would come right over and knock on each tenant’s door until he found the thief.

“Yeah, I know who. On top of that I found my car gone when I went out to park it—but who cares. I don’t want the junker back even if you do find it, like you did the other two times. Hell,

I’m not going to even report it, but how will my wife and I eat tonight?”

“Well, you’ll have to get the groceries again. Who do you think did it?”

“For Chrissakes, how’m I going to go? In a cab? I’ve got to go to work.”

“I suggest a cab, Mr. Rebollo,” Benek said.

“Yeah, I guess.”

“Who do you think took the groceries, Mr. Rebollo?” Benek asked again, staring at the steam coming up from his coffee cup.

“Who else? The super!”

“Come by and file a complaint.” He wanted to ask the man why he was careless enough to leave his groceries in the hallway of his house, but refrained. The overworked and unhappy man had probably always left his bags in the hall and been lucky enough to believe that a law of nature was at work protecting him. “And do you or don’t you want to report your car stolen?”

“Nah,” the man said, and the dial tone finished up for him.

The phone rang again at once.

“Detective Benek. Name, please.”

“My son’s bike was just stolen!” a woman shouted. “How’s he gonna get to school?”

“You’ll have to come down and report it.”

“He needs the bike!”

“I sympathize, but it’s the only way.” He had once given out the usual story about how many bikes were stolen each year and if the police followed up on each one they’d never do anything else, but he no longer had the heart to tell them that not much could be done, that the bike was gone unless they could provide a lead or hunt it down themselves, as in a movie he had once seen, but those who had that kind of luck never called back to tell him about it. “Come over,” he said, trying to sound helpful, but she was gone.

The phone gave half a chirp and stopped, then sang like a sparrow.

“Detective Benek here. Name?”

Silence. He hung up and tried his coffee. It was still too hot, but he tried to choke some down before the next call came in, wondering how much paperwork he could get done before a call sent him out, or Captain Reddy decided he should follow up on something from yesterday, or even last week.

At 8:40 he turned on his terminal and scrolled up his cases, looking through the new annotations for anything that might suggest further investigation. Down the hall, he heard Silvera, Abrams, and Didsbury arrive at their partitions, each making his own characteristic noises. Silvera was very quiet as he sat down in his chair, and was probably grooming his black hair with his pocket comb. Abrams started to blow his nose, then began to open drawers in search of more Kleenex. Didsbury cursed softly to himself as he searched for notepaper. Benek waited for him to give up and wander over to Silvera for a quick gab, often about a woman.

“What’s with you?” Benek heard Silvera ask.

“I dunno,” Didsbury began. “Last night I had one suspect threaten to jump out the winda if I came into his place—over a mild assault complaint, would you believe? Another guy—just a crank caller, really—was hiding under the bed when I found him and just wouldn’t crawl out.”

“So?” Silvera asked. “Little stuff like that bothers you?”

“Little stuff like that wears away at you. It wears you down and wears you out. Little stuff like that can bury you.”

“How so?” Silvera asked. He was always in a good mood in the morning, ready to lead anyone on into a swamp of questionable assertions. “Wears you down if you let it. I don’t let it.”

“Makes you wonder about people when you don’t want to. You have no say in how it wears at you.”

“Don’t sweat it. Little stuff takes up time and gets you through to retirement.”

“Yeah, you’re right, you gotta use up the time. Who gives a shit. I just wish I wouldn’t think about it so much.”

“Then don’t.”

There was a sudden silence. Didsbury had gotten his fix of whatever reassurance he needed and was back in his alcove, ready to go.

A door closed loudly at the end of the hall, signaling that Captain Reddy had arrived.

All the phones, including his own, started to chirp, and people began shouting in the main room downstairs as citizens and suspects started to come in, pounds of flesh and those looking to get their pound of flesh. It was just 9:00 A.M. as Benek reached for the phone and knocked his now cold coffee into his lap.

He sat there for a few moments, thinking as he mopped it up with a paper napkin that there were people who felt things keenly, as a result of deep observation, and people who resisted their feelings and prattled about how over-insistent the first kind of people were. To this second kind of person every strong reaction was a dramatic exaggeration of some kind. They were sincere and cool, this second kind, and he did not blame them; feelings could be misleading, but then so could rational constructions that had little or nothing to do with reality, or just enough connection to fool you. The “pitch” of self-possessed people seemed to be set too low, but they had no way to know it, since in their condition they dismissed sharp contrasts.

Benek had tried to imitate the second kind of person, to be dispassionate and controlled, never to get personal with himself, especially about himself. But his self-rule was failing, and had been failing for some time before the unavoidable lessons of his job. A conquering horde was encamped on his frontiers, and had for years been sending threatening emissaries to his inner court calling for surrender; now they were sending raiding parties into his heart. He was beginning to see that the cool-headed ones of the world were rarely poor but always impoverished in a way they didn’t care about. They lived by the law, but they were free of honor’s demands, by which individuals were joined to each other’s domains. The coldest ones ruled the world; they ruled the law, and did not knock over their coffee in the morning.

Captain Reddy tried to be a cold one, but he failed in joining the coldest. Silvera, Abrams, and Didsbury were only pretending and suffered in private. They were what the ruling hierarchy wanted, except when the violence and graft got out of hand and became partially public; then the top wanted what the thinkers called socially concerned officers with some heart, fellow citizens of the people they policed, living in the same streets as the law-abiding and the waiting criminals, officers who would go home and be seen to be tired out from their job, send their uniforms and laundry to the local cleaner, pay the same rents, get married and raise the same new hostages to fortune.

Who was anybody? How did anyone know that there were others like them behind peoples’ faces? Clues led to assuming that awarenesses boiled behind eyes, but no one knew in the same way as they knew themselves. Even that sense of one’s innards seemed too little. He was not an empty shell because there was a spongy three pounds of stuff inside that called itself a brain, an electrical filing cabinet and switching device; but where was the thing that knew itself and knew that it knew? It flickered in the soft circuits, looked out through light-adapted watery eyes, felt with bony fingers and porous skin, smelled through a nose that collected dirt on behalf of the lungs. But the awareness was trapped, once believed to have come from somewhere else but still trying to escape... perhaps alone, the only one of its kind, lying to itself about all the others. There was no one home anywhere. Just things of some kind imagining themselves...

“You’re all alone,” his drunken father had once said to him, sprawled on his cot in the basement. “It’s all a put up job around you, made to fool your eyes. There’s no one out there. Take my word for it, son, there never was anyone there. You don’t believe me? Go look outside. I mean really look outside. There’s nothing there! It’s all dark!”

“Then why are you talking to me?” Benek had asked.

The drunk had roared with laughter and said, “You don’t get it, do you?” It had not been a question, but an arrogant assertion of fact. Logic was long gone. “You really don’t get it at all?” he had repeated, as if catching a simple mistake in addition.

“What?” Benek had asked.

“I’m talking to myself,” the drunk had

mumbled as he fell asleep.

2

“I want to ask you about this autopsy report,” Benek said from the doorway. The large office was well stocked with plants, clearly belonging to a man who had made something pleasant of his workplace.

The overweight, balding coroner did not look up from his desk. “You can want all you want, but my open door does not mean you don’t have to knock. Who are you?”

“Sorry,” Benek said as he came forward and put the report on the man’s neatly arranged desk. “Detective Benek, homicide, 6th Precinct, annex A.”

“Annex A?” He smiled to himself, as if the annex address had a special meaning.

“Yes,” Benek said.

The coroner glanced at the file and sighed. “It’s exactly as I put it down, Detective Benek.”

Benek said, “I’d like more on this one.”

“More of what?” the man said softly.

In the week since the report had arrived on Benek’s desk, no one at the precinct, including Captain Reddy, had shown the slightest curiosity about the odd details. So Benek had decided to use some of the initiative that Reddy was always prattling about. If something smells, Reddy would say, then follow it up—but try not to waste the city’s money.

The coroner looked up finally, obviously irritated. “What do you want from me?” His blue eyes were youthful, and seemed happier than the rest of his face, as if he were living somewhere else. “Why complicate your life and mine with this nonsense?”

“What’s your opinion?” Benek asked, trying to sound polite.

The coroner smiled. “Don’t waste any more of our time on what’s obviously a medical student’s prank.”

“But your report seems to rule that out.”

The coroner sighed again and put his work aside. “Sit down, Detective.” The look of living somewhere else faded from his eyes and he seemed resigned to the here and now.

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time Stranger Suns

Stranger Suns Black Pockets

Black Pockets Brute Orbits

Brute Orbits Cave of Stars (Macrolife Book 2)

Cave of Stars (Macrolife Book 2) Macrolife

Macrolife Empties

Empties Heart Of The Sun Star Trek 83

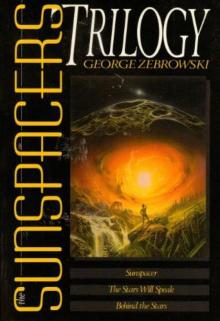

Heart Of The Sun Star Trek 83 The Sunspacers Trilogy

The Sunspacers Trilogy