- Home

- George Zebrowski

Heart Of The Sun Star Trek 83

Heart Of The Sun Star Trek 83 Read online

Thank you for purchasing this Pocket Books eBook.

* * *

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Pocket Books and Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

About the Author

To our friend, Ted Brock, who learned from everyone but always knew how to watch Star Trek

We may choose something like a star

To stay our minds on and be staid.

—Robert Frost

Chapter One

“RIGHT HERE—” Commander Spock said as he pointed to the flashing dot on the sector display, “—in the cometary ring of this solar system, there is an object that does not belong.”

He paused, as if for dramatic effect, though Kirk knew that his science officer was above such gestures. Spock continued. “It is clearly artificial, Captain, a fact confirmed by its heat signature, which is increasing too precisely for a natural source.”

“Could it be Romulan?” Kirk asked. They were close enough to the Neutral Zone between Federation space and the Romulan Empire for that to be possible.

“Unlikely, Captain. Our first indications were that it was a planetary body that had long been part of the ring. Our records show it has been there for some time. There is no evidence to suggest the Romulans would have intruded so far into this sector.”

Kirk looked at his friend, and for a moment shared with him the rush of discovery that was curiosity’s reward. But the moment passed, and he said, “Unfortunately, we can’t even think of investigating that object until after we complete our mission on Tyrtaeus II.”

“Understood,” Spock replied, peering at the display, and for an instant, James Kirk remembered when he had once thought that he would never really know the Vulcan as he knew Leonard McCoy, Montgomery Scott, Uhura, or the other members of his crew. Once, he had believed that Spock would always be a stranger, as he was to most human beings. Kirk had wondered if the distance between them might widen into a gulf.

But he had learned to see through Spock’s inscrutability, just as he could gaze into Lieutenant Uhura’s dark eyes and see if some private, unspoken concern was worrying her, and know from the cheerful, enthusiastic look on Hikaru Sulu’s face that the helmsman was about to launch into a discussion of his latest hobby. Spock’s raising of his eyebrow when confronted with yet another example of human foolishness betrayed not only his wonderment at human irrationality, but also his amusement at such illogical behavior. Spock had a good sense of humor—for a Vulcan, Kirk mused. Of course, his stoic friend would never acknowledge that openly.

The composed but intent expression on Spock’s face now told Kirk that his science officer was extremely curious about the unknown object on the display.

“Investigating that object,” Kirk said as he gestured at the sensor display screen above Spock’s computer, “would be a lot more interesting than this mission’s likely to be. At least well have something to look forward to after we’re done on Tyrtaeus II, right, Spock?”

Spock was silent. Kirk suppressed a grin. The Vulcan would sooner die than admit how eager he was to get the diplomacy out of the way, so that the crew could move onto what they did best: exploring the unknown.

Occasionally Kirk could grasp his comrade’s unspoken thoughts only as one would observe icebergs floating down from their calving waters in Earth’s polar regions, seeing only the small portion that showed above the surface while sensing the leviathan hidden below.

“I’m picking up a message from Tyrtaeus II,” Lieutenant Uhura said, interrupting Kirk’s reflections. “It’s exactly the same as the one we picked up earlier.” She frowned, then recited the message. “ ‘We look forward to restoration of our data base soon—Myra Coles.’”

No salutation, Kirk thought, no niceties of expression, no hint that the Tyrtaeans might be grateful for any aid the crew of the Enterprise could give them,

Myra Coles, the computer had informed him, was one of the two elected leaders on Tyrtaeus II, although she had no title. Tyrtaeans, according to Federation records, did not bother with titles.

“There seems little need,” Spock murmured, “to send the same message twice, especially since we acknowledged the earlier one.”

“I think,” Kirk said, “that they just want to remind us of how annoyed they are about this whole business, but without engaging in any unseemly displays of emotion. You have to admit that their earlier messages were masterpieces of a sort. I wouldn’t have thought it possible to express so much anger and bad feeling in so few words, and so simply.”

Spock lifted a brow. “The Tyrtaeans have a reputation for practicality. They would not have wanted to waste either our time or their own with a long message.”

“Yet they’ll waste time by sending it twice,” Uhura murmured.

Spock glanced toward the communications officer. “They are human, Lieutenant, the descendants of settlers from Earth. That is undoubtedly enough to account for any apparent contradictions in their behavior.”

Ouch, Kirk thought. If I were in a pettier mood I could remind him that guessing games are illogical. But Vulcan guesses were pretty reliable, he reasoned. Especially Spock’s guesses. Maybe it was the human in Spock that made him capable of his often brilliant intuitive leaps.

In any case, Kirk reminded himself that the triumph of Vulcan rationality had not been complete; traces of Vulcan’s violent past could still be found in such customs as the koon-ut-kal-if-fee, or in the kahs-wan survival ordeal. Still, the Vulcans could be admired for the stability they had achieved, given the ferocity of their early culture. The Vulcans, unlike the Klingons—and unlike some human beings, Kirk reluctantly admitted to himself—had come to understand that violence was not something to glorify and celebrate. That was the way of the galaxy’s intelligent life-forms; a net gain here and there, with the evolutionary legacy still in control, a dead hand guiding intelligences that were not yet ready to remake themselves and to be responsible for everything.

Kirk smiled inwardly. Spock himself had once said something much like that to him, in almost the same words. The Vulcan was not as naive as he sometimes seemed, and occasionally some warmth could be glimpsed in his usually impassive face. Naivete was his way of keeping an open mind.

Spock exhaled softly, almost sounding as if he were sighing with exasperation, unlikely as that was. Kirk suspected that his science officer had even less enthusiasm for this routine mission than he did.

They were on their way to Tyrtaeus II to restore that planet’s data base because of an unfortunate accident. During a routine update of the data bases of a few colony worlds, some Federation technicians had accidentally downloaded an old, long-hidden, and undetected virus along with the revised data. The virus had destroyed not only five planetary data bases but also the programs that ran the subspace communications systems of those worlds; new data bases could not be downloaded until the subspace systems were repaired on site.

The Enterprise had been going from one star system to another, repairing the subspace communications systems of each affected colony, th

en overseeing a new download from the Federation’s database on Earth. That, Kirk thought, had been the easy part of a fairly tedious mission, which would at last be concluded on Tyrtaeus II.

The hard part was restoring the local history and recorded culture of each world, since that would have to come from other sources. Fragile and perishable documents had to be located, history and folklore rewritten and rerecorded, literature and poetry rediscovered and reproduced. After completing the straightforward work of repairs and downloads, all that Kirk and his personnel could offer was a certain amount of detective work. Some data could be recovered from the repaired data base and retrieval systems, but people trained in archaeology, historiography, and anthropology would have to ferret out the rest. The restoration would require a number of searches, and they had to face the possibility that some data might be permanently lost.

Spock had a theory, which he had been testing as often as practical, that the virus had not destroyed all of the data, but had merely “hidden” at least some of it. If he was even partially right, Kirk knew that a lot of hard work in search of physical records could be avoided.

The people on the four worlds that the Enterprise had already visited had been understandably irritated, even angry about the damage to their data bases. Kirk recalled how distressed the Lurissan Guides, the governing body of Cynur IV, had been when he had first met with them. The people of Cynur IV had a reputation as some of the warmest and most hospitable beings in the Federation; but the Cynurians Kirk had encountered had taken every opportunity to gripe and rail against the Federation for its carelessness; their hospitality had been grudging at best. He had no reason to expect the Tyrtaeans to be any more amenable, especially when they learned that perhaps not everything in their data base could be restored.

They also, Kirk reminded himself, had other reasons for not welcoming Starfleet personnel. Unlike the other four affected worlds, the Tyrtaeans had joined the Federation grudgingly. Their ancestors had left Earth a century ago; the Federation was a reminder of the world they had sought to escape.

Spock was still studying the strange object on the sensor screen.

“It’s ironic,” Kirk said. “The people of Tyrtaeus II pride themselves on withstanding adversity with forbearance. They scorn luxury, and think public displays of strong emotion are offensive. They have the reputation of being one of the more stoic and severe people in the galaxy. Now they are faced with a threat to their most ethereal artifact—their recorded culture. And that part of their civilization—the least practical and most unnecessary part—that is what they have complained about most keenly.”

“I do not find that ironic, Captain,” Spock said without turning from the screen. “What is most necessary for any being, all other things being given, is to maintain its identity, which is also essential to any culture. Irony, as I understand it, seems a superficial interpretation of the situation in this case. Least practical and most unnecessary is not how their loss should be described. What would you have the Tyrtaeans conclude? That they can do without what is apparently lost?”

Kirk considered for a moment. “You’re right, of course. They might complain a bit less, though.” He leaned closer to Spock to view the screen, where the heat signature of the mysterious object was still increasing. “We’ll have to find out what that is,” he added, “as soon as we’ve finished our job on Tyrtaeus II.”

Spock nodded, as if approving of his curiosity, then said, “I trust that it will be enough for the Tyrtaeans to learn that less was lost than they feared. It is fortunate that they overcame their reluctance and downloaded much of their data base in recent cultural exchanges. We will be able to restore all of what they downloaded at that time.”

“Some of them won’t be satisfied, Spock. Much of their cultural identity, as you say, was in those records.”

“Kind of an insular culture,” Uhura murmured, “from what the records indicate.”

“No more so than those of some other colonies,” Kirk said.

“But the Earth folk who came here wanted to be left entirely alone,” Uhura continued. “According to our records, their admiration of self-reliance is so extreme that they seem to avoid any activity that might tempt them into dependence. They have less to do with other worlds than any other culture I can think of.”

Kirk straightened. “We have to respect any colony’s insularity, Lieutenant. Uniqueness can be inconvenient in the short run, but the Federation has to respect it if we’re to have reliable cultural partners in future times. As Mr. Spock said, a culture’s identity is essential, and must not be threatened.”

“Quite right, Captain,” Spock said, in what some would have regarded as a slightly patronizing tone; Kirk took the comment for what it was, a simple statement of fact. Spock was, he supposed, a superior being in a way. But not so much as to sever all bonds of sympathy with his comrades. Spock might strain those bonds of kinship, but they would never break.

* * *

As Captain Kirk turned away from the sensor display and resumed his post at his command station, Spock heard Lieutenant Kevin Riley say, “Entering standard orbit around Tyrtaeus II, Captain.” Kirk nodded at the navigator, then waited for Lieutenant Sulu, who was seated at the helmsman’s station on Riley’s left, to confirm.

Spock gave only part of his attention to the routine activity on the bridge; he was looking back to his computer display screen as often as possible, where the heat signature of the unknown object was still increasing, telling him that the mysterious device was generating large amounts of energy.

“Standard orbit achieved,” Hikaru Sulu announced from his forward station.

The bridge was oddly silent for a moment, Spock noticed.

“Mr. Spock,” the captain continued, “are you with us?”

Spock was turning away from the screen when he saw a change on the long-range sensor scan. “Just a moment, sir,” he murmured, leaning toward the screen again.

There was no doubt about it; the strange object had changed course.

“Captain,” Spock said, “the unknown object I have been observing has changed its orbit. It is now moving sunward, on what is clearly a collision course with the star.”

“What?” Kirk said as he turned in his chair. “Then it definitely isn’t a natural object.”

‘This is further confirmation that it is not natural”

Kirk frowned. “Lieutenant Uhura,” he said, “open a hailing frequency to Tyrtaeus II.”

“Hailing frequency open,” Uhura announced.

The head and shoulders of a man appeared on the large bridge viewing screen. The man’s face was lean and fine-featured, framed by short, dark hair. What Spock could see of his brown shirt was plain and unadorned. The man narrowed his eyes slightly, and his mouth twitched a little before he spoke.

“Aristocles Marcelli,” the man said in a strained tone that Spock recognized as that of someone struggling to control his rage.

* * *

Kirk slowly got to his feet. “Aristocles Marcelli,” the man said again in his flat voice, and Kirk quickly understood that the Tyrtaean was telling him his name.

“Captain James T. Kirk of the Enterprise,” Kirk responded. “We’re here to …”

“I know what you’re here for.” Aristocles Marcelli sounded merely irritated this time.

“Sir, we …”

“We don’t hold with titles here, Kirk, even ones like ‘sir’ or ‘mister.’ Call me Marcelli, or even Aristocles, if you like.”

No greeting, no polite commonplaces, no attempt at even a semblance of warmth or courtesy. There was plain speaking, and there was rudeness; this man didn’t seem to grasp the distinction.

“I trust that you’ll be quick in replacing our loss,” the Tyrtaean continued.

Kirk felt like a junior engineer reporting for nacelle cleaning duty. “We’ll do our best— Marcelli.”

“That kind of answer always sounds like an excuse in the making, Kirk. You don’t antici

pate any problems, do you?”

“We don’t anticipate any problems beyond the ones we can reasonably anticipate,” Kirk said.

“In other words, you’re expecting some problems—just not any new problems.”

The Tyrtaean seemed to be doing his best to be annoying, which did not seem consistent with the stoicism these people allegedly practiced. Kirk reminded himself that the reputedly friendly people of Cynur IV had only begun to warm to his personnel just before the Enterprise was to leave their system, and that all of the affected colonies had deeply resented the loss of their data bases. There had been no available target for their resentment other than the personnel of the Enterprise. Once again, Kirk decided to make allowances.

“As you well know,” Kirk said, “we can’t overcome the lack of physical backups. If you have lost certain kinds of data, we can’t recreate that information from nothing. There has to be—”

“And who put us into this situation?”

Kirk kept his composure, although it was becoming more of an effort after dealing with the reproaches of four resentful worlds. “We’ll do the best we can. I can promise you that, Marcelli. But we can’t work miracles.”

“Captain,” Spock said, coming forward to face the viewscreen, “may I make a suggestion?”

Kirk glanced at him. “Of course.” He motioned to Spock. “This is Commander Spock, my science officer and second-in-command of the Enterprise.”

Marcelli’s brows shot up. “A Vulcan! Maybe now we’ll get somewhere.”

Kirk tried hard not to look annoyed.

“I do not wish to offer false hope,” Spock said. “I merely wish to recommend that you do not give up on the physical presence of certain kinds of data. Such data may still exist in unexpected places on your world. For example, the inhabitants of Emben III were certain that several of their most highly prized narratives were lost. Records dating back to their earliest settlers were thought to have existed only in their damaged planetary database.”

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time Stranger Suns

Stranger Suns Black Pockets

Black Pockets Brute Orbits

Brute Orbits Cave of Stars (Macrolife Book 2)

Cave of Stars (Macrolife Book 2) Macrolife

Macrolife Empties

Empties Heart Of The Sun Star Trek 83

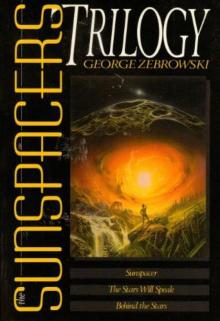

Heart Of The Sun Star Trek 83 The Sunspacers Trilogy

The Sunspacers Trilogy