- Home

- George Zebrowski

Black Pockets Page 2

Black Pockets Read online

Page 2

“Nonsense,” he managed to say reassuringly, but the word only seemed to reproach his own impulses. “You’re just escaping from overwork. That’s what these jumping dreams mean. How are things at your job? You have taken your leave, haven’t you?”

“I can’t take off just yet,” she said pitiably. “Maybe next week.”

“When was the first time you had this jumping dream?” he asked, making a mental note to check a few facts in her file.

She swallowed hard. “They’re not dreams,” she said softly, staring at the carpet.

“Please go on.”

“First time was when I was a girl. My father came to my room and began touching me. I was terrified. Later that night I woke up and found myself in a neighbor’s house.”

She did not look at him, and he knew that she was still her father’s prisoner. The need to escape him had set a pattern of wish fulfillment. Any kind of pressure, even that of the workplace, still triggered the abused child’s dreams of escape. Slowly, he would make her understand.

“I can help you,” he said. “In time you won’t have these dreams, and you’ll know that’s all they were. It may seem hard for you to accept that now, but you’ll learn it for yourself.”

A look of anger came into her face as she looked up at him. She bit her lower lip, as if confronting something within herself. “I hated him for touching me, and I hated him even more later, when I understood.”

“Did you ever say anything to him?”

She shook her head, unable to speak for a moment. “He died before I could. I don’t know why I lied to you about his still being alive. I’m sorry.”

“That’s okay, you’ve repaired it.”

She smiled desolately. “He got away from me, didn’t he?”

“You’re getting better,” he said during their fifth session. “No dreams for weeks now.”

She shrugged. “It’s happened before. Doctor, you must come to my place and wake me before I jump again, tonight.” There was no doubt in her voice. It worried him that she still refused to accept the fact that she was only dreaming of jumping.

“You don’t expect me to sit at your bedside, do you?”

“I’ll pay you extra, but it must be tonight.”

“I can’t get a nurse on such short notice.”

“Then give me a release to sign, anything. I can’t be alone tonight. I can feel it coming on.” She took a deep breath, and her right hand shook slightly.

“Perhaps you’re right,” he heard himself saying. “If I can wake you up, then you’ll be sure it’s just a dream.”

“If you can do so in time.”

“What time should I arrive?” he asked.

“No later than eleven.”

They sat quietly for a few moments. She stared past him, out the window. He tried to ignore his feelings for her, think of her only as a patient, but he couldn’t shake her attraction. He wanted to hold her, kiss her gently, free her from her past. Warnings crowded into him, but he ignored them.

Her East Side apartment building was bright with lights when his cab pulled up. The architecture reminded him of egg boxes. Soft creatures called people lived in the private chambers. He felt a bit useless and infantile as he paid the driver and walked toward the glass entrance. Doubts slipped through him. How could he presume to know another’s mind? They were all ever-changing labyrinths, his own included. His professional knowledge permitted nothing more than a form of organized insisting, a sublime version of parental scolding. His training was a weak imposition on a beast that was ancient and sure in its ways, always ready to overcome its displacement. It lay coiled and waiting for everyone. He was no exception.

The doorman’s scrutiny made him uneasy, but finally he was in the elevator, on his way to the thirtieth floor. She was waiting for him at the door of her apartment, dressed in jogging clothes, newly laundered, by their smell.

“I’m really beat,” she said, as she locked the door and led him through the living room into the bedroom. “All my keys are in the safe. Here’s the spare. Check the front door again, so you’ll know I can’t get out. Is that scientific enough for you?” The sarcasm in her voice wounded him.

“You’d have to fly to get out of here,” he said, looking through the window at the East River.

“There are books by the desk,” she said, getting into bed. “The light won’t bother me.”

She closed her eyes. He stood over her, watching her face, waiting for it to relax, but there was no change. It remained composed, oblivious to his eyes. He felt lost, on guard over a plundered fortress.

There seemed to be a lump in bed with her. He waited, then lifted the blanket slightly. She did not react. He peered under and saw that she was holding a small fluorescent light, the kind mechanics used when they worked under cars. He put back the blanket and went over to the desk.

He sat down and went through the motions of selecting a book from the small bookcase at his left. There was nothing of immediate interest. He sat still, listening to her gentle breathing and began to grapple again with his feelings for her. Tenderness struggled with simple desires. It seemed that she was everything he had missed, making him feel deprived and alone. It was an old pattern with him, going back to his college days. He had considered it broken by the time he had entered medical school, yet here he was again, all but alone in a room on a Friday night, fantasizing as he had done in his freshman days.

There were some papers on her desk blotter, and he found himself looking through them to distract himself from self-pity and the thought of her in the bed behind him, warm and soft under the covers. There was an old clipping, a death notice giving the date of birth and the date of death, including the man’s profession and the name of the cemetery where he was buried. The yellowing paper dropped from his fingers as he realized that he could no longer hear her breathing.

He turned around, but the desk light had affected his eyes, making the room black. He waited, then got up and went to the bed.

It was empty.

He looked around, wondering if she could have crept past him in the dark, but then he saw that the covers had not been disturbed.

He pulled them down. She was gone, and she had taken the light with her.

He rushed out into the living room and checked the front door. It was locked, and the key was still in his pocket. By all rational evidence she was still in the apartment with him—unless she had fixed the covers quietly and used another key to get out. He would have heard her.

“Katya!” he shouted, using her name for the first time.

There was no answer.

He searched the kitchen and bathroom, all the closets and under all the furniture. She was here, he told himself, wondering if he couldn’t see her because he’d gone insane. She was hiding from him, attempting to convince him that her delusion was true.

“Katya come out!” he shouted.

Finally, in the silence, he remembered the clipping and knew what he had to do.

The cab let him off in Brooklyn at 3:00 A.M. He found the cemetery park, but it took him over an hour to find the grave and start digging. His flashlight kept fading, but he finally uncovered the coffin. He stared at it, breathing heavily, nearly convinced that he was mad. A breeze swirled a few fall leaves around him, then subsided. He looked around to see if anyone had noticed him. He was probably too far inside the park to be seen from the street.

He drew a deep breath and started to pry open the casket with his spade. The lid wouldn’t come up, then flew open with a jarring creak. Bright fluorescence shot up from inside like daylight, dazzling him.

As his eyes adjusted, he saw her. She was grasping her father’s skull with both hands. The skeleton was disordered. Her eyes were wide open, staring up at him from the prison of her dead body.

She had awakened in total darkness. He saw her turning on her light and screaming in its lurid, white glare as she struggled with the dead, realizing with terror that no one could help her before

the air in the casket ran out. She had known where her father was buried from the old clipping, and she had jumped to this same park recently; but her conscious mind had not suspected that she would jump into the coffin, even though something had prompted her to bring the light. She had expected to find herself in another dark, empty house somewhere.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” he asked uselessly, his voice breaking. She had told him that she was going to die. “I could have been waiting here to dig you out,” he said, reaching down to touch her cheek for the first time. It was cold. Gently, he closed her eyes.

If only he could have believed her. The girl had jumped to escape molestation. The woman had cast about, seeking to confront her father, only to learn that he had died. Cheated, her unconscious had found a way to invade his final resting place and tear apart his bones. Her deepest self had also wanted to die, he realized as he imagined her screaming and choking in the earth.

“Come on, get up out of there,” he said, childishly wishing that this could be only an odd rebirth ritual, of the kind prescribed by some of his wilder colleagues. His body shuddered in the cool, damp air.

Moths and insects were zeroing in on the column of light standing out from the grave. He picked up the fluorescent pack and tossed it away. What could he do? She was gone, and there was no way to prove what had happened. The police would conclude that she had been asphyxiated and brought here. If he called them now, he would be the only suspect, telling an utterly fantastic and unbelievable story. It would mean a trial and the end of his practice. His life would be over if he went to prison. If he left the grave open, she would be found, and sooner or later he would be questioned.

He closed the coffin, telling himself that he had committed no real crime; better if she were never found. The fluorescent light flickered on the damp grass as he climbed out and began to fill in the grave.

When he was finished, he looked around at the dark cemetery. How many sons and daughters slept with their fathers’ corpses, clutched at their mothers’ dry breasts, or tore at their siblings’ throats? A study of case histories from the missing-persons divisions might reveal where other jumpers could be found.

She would be missed eventually, and they might come to question him; something at her office or at her apartment might tell the police that she had been his patient; but there was no reasonable chain of criminal motives or actions that would lead them to her body. She would become just another missing person.

He brushed himself clean as best he could, disposed of the two lights and spade in different waste cans, and wandered off in search of a taxi, as far from the park as possible.

The cab’s radio played love songs all the way home.

The Wish in the Fear

FRANK’S LEFT UPPER TOOTH HAD BEEN CAPPED in 1970, after he had cracked it by falling flat on his face during a racquetball game. Earlier that year he had seen a man with a broken front tooth on the bus, and had wondered what it would be like to have a broken tooth. It was as if his future were casting a shadow into the past.

At least once a year since then he had dreamed that his cap had come off, because it seemed to him that every year beyond the first ten seemed too many for such a thing to stick to his filed-down tooth. Losing his cap was the one nightmare that continued to convince him of its truth, and he was always grateful to wake up to its unreality.

But this was only one of many trivial fears he would develop. Another involved sharp objects and the hidden nature of accidents. Were they fixed, waiting to happen at the appointed time? he asked himself as he idly imagined putting out his right eye with a pencil. Whether he could muster the courage to do so deliberately interested him, but the more frightening possibility was that a series of ordinary, even logical steps might lead to it surreptitiously, remaining concealed until it was too late. He suspected that there was some train of events that might make it happen, some arcane dovetailing of circumstances that would make it come out that way, or even worse, convince him that it was the necessary thing to do.

As a boy he had gone up to the cliffs that faced the apartment houses in the South Bronx just below the Grand Concourse, and had stood there on the edge of the loose slate piles with his back to the sheer drop, glancing over his shoulder at the empty windows to see if anyone was watching. He did not slip and did not want to, but it was hypnotic to imagine himself lying in one of the backyards below, his broken body motionless in a pool of bright blood on the paving stones. He could still see himself there, balancing on the balls of his feet.

Over the years he became adept at imagining that what he saw happening to other people might also happen to him. He was both attracted to and repelled by most of these reveries, but was unable to shake the foreboding that sooner or later some, if not all, would become realities for him. When he saw any kind of accident overtake someone, it was always a possible harbinger of his own fate.

But he lived a life remarkably free of mishaps. Instead he became a collector of other people’s fears and phobias; and however terrifying they might be while he was in their thrall, nothing ever happened to him. He came to accept this as the way things were with him, and looked forward to the next one as people do to a concert, play, movie, or television show.

His most intense encounters with people stayed with him, becoming a collection of recurring dreams. Each new collision became a candidate for his growing labyrinth of shared fears and phobias. He sometimes suspected that the answer to what made one stay and another flee from his dreams was the secret of his life, the key that would open the door to himself, but he was content to hold it dear and unknown, hidden deep within himself.

He tasted the summer rain in his dream as the wind blew drops into the gazebo behind the pool. Everyone at the mountain resort had fled into their cabins and into the main building, but he had stayed out to watch the rain.

He heard the expected footfalls on the wooden steps behind him and turned to see Vera, still dressed in her white blouse, white shorts and sneakers, shaking water out of her shoulder-length blond hair as she looked shyly at him. He was nineteen and in college; she was just going on seventeen. She was here with her parents and brother, and they were all very protective of her developing sexual vulnerability, so he had kept his distance, content to watch from afar her stocky, athletic form filling out her well-pressed shorts and blouse.

“Hello,” he said with a nervous breath.

“Hi,” she answered, smiling angelically, and he felt once again that a hidden script was being revealed for him to speak, one line at a time, so he wouldn’t know what came next, even though he had played this scene with her many times before. The words, expressions, and some of the physical movements varied, but the differences were unimportant.

She leaned back against the railing and took a deep breath. He came over, leaned back next to her and said, “Some rain. It might get cloudy for the next two weeks. That sometimes happens up here.”

“Oh, no. I hope that doesn’t happen.”

He turned and gazed at her. She looked back as if searching his face for something, and he knew that she was afraid of being alone with him.

“I’ve seen you around,” he said, glancing down at her pressed shorts, which stood away from her smooth, still slightly heavy but attractive thighs.

“Don’t look at me like that,” she said. “It makes me nervous.”

“But I like the way you look,” he answered gently, and saw her swallow, and knew that she felt pride and guilt about her emerging good looks. As she matured and gained her full growth, she would become a blond goddess and know power over boys and men; but for now she was still unsure, unable to consciously attract or humiliate, also following an ancient script that startled and intrigued her. “I think you’re beautiful, but I couldn’t tell you around your family.”

She grimaced and smiled, then looked across the resort grounds as if her parents might see her from their cabin, but relaxed, realizing that they did not have a clear view of the pool. He beg

an to gaze at her adoringly, but looked away as she became aware of the desire that was growing in him.

He moved closer to her and took her hand. She tensed, then blushed.

“You’re very beautiful,” he said.

“You’re just saying that,” she whispered.

“No—it’s true,” he said, leaning closer. She drew a deep breath and slid away from him on the rail, trying to smile knowingly, but it came across as sheepish, shy, and green.

He looked at her caringly, and something inside her seemed to break as he moved nearer and was about to kiss her. She took a deep breath and looked away from him.

“No,” she said with a sob, “I can’t.”

“Why not?”

“Before,” she mumbled, looking as if she might cry, and he felt pity and concern for her, and the impulse to protect her, to hold her, flattered that she was showing these feelings to him. He looked into her eyes and his gaze locked with hers, trapping him in a strange prelude to a dance that she would teach him.

“I went out last year,” she started to say awkwardly, looking at him as if she had to expel feelings that were stuck within her. “He came to dinner at my house. My parents liked him, my little brother liked him, my friends. We went out for a month, and then he broke it off and it was... horrible.” She choked on the last word and tears ran down her face. “And I couldn’t tell anyone that he’d touched me and kissed me, and that I wanted him. I was so afraid. I’d thought he wanted to marry me, to be with me forever, but it was all a lie. I don’t want that again.”

She was silent, and he realized that it had been all or nothing with her, with no in between; and that this demanding familial finality had driven her first boyfriend away.

“It’s okay,” he said, putting his arm around her as she stopped crying, accepting the fact that there was nothing very interesting about her; not her white shorts and tanned legs and arms; not her blond hair or blue eyes. The silkiness of her fled from his mind before her raw need. She was hungry to swallow him. There was nothing personal about what might have been between them, only a role that she expected him to assume; a hundred other boys would do just as well.

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time Stranger Suns

Stranger Suns Black Pockets

Black Pockets Brute Orbits

Brute Orbits Cave of Stars (Macrolife Book 2)

Cave of Stars (Macrolife Book 2) Macrolife

Macrolife Empties

Empties Heart Of The Sun Star Trek 83

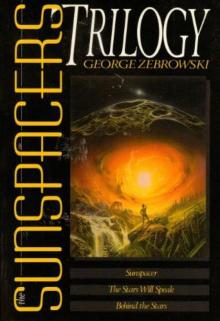

Heart Of The Sun Star Trek 83 The Sunspacers Trilogy

The Sunspacers Trilogy