- Home

- George Zebrowski

Black Pockets Page 5

Black Pockets Read online

Page 5

Rick looked toward the picnic table where the two men had sat down. There was no sign of them.

“Where are they?” the woman in jeans demanded.

“Can anyone drive a bus?” asked the man across from her.

Rick knew that he could drive the bus, if necessary. Suddenly the driver came back, threw himself into his seat, and closed the door. He gunned the engine and pulled out from the rest area. The other driver did the same.

The buses began to run side by side in the night, each trying to leave the other behind, and failing. Rick wondered what the two drivers had said to each other, then saw that the buses were drifting toward each other, as if trying to merge. Sparks jumped between the coaches, crackling and lighting up the road with flashes of blue electric glare, and he glimpsed himself staring through the other window. People shouted and cursed in panic.

“Get away from it!” a man shouted to the driver.

“Shut up!” he answered. “Something’s pulling us together.”

Together, Rick thought, wondering if the two buses had been one and the same just recently, and were now struggling to regain that state. He did not feel diminished by half, but would he even remember what had been subtracted?

The buses raced less than a foot apart. He stared at himself across the distance, at the starlit and shadowed face gazing back at him, and realized that there was a whole world behind the man in the other bus, but his movements did not match his own, and were not a mirror image, either, from what he could see. A blue glow came up from the roadway.

Both buses slowed as they neared a causeway that led out across a lake. The other bus pulled ahead suddenly, went through the railing without shattering it, and continued on a phantom road. He realized that there had to be a road across the lake, even if he couldn’t see it. The lights of the bus were not reflected in the dark water. The bus receded and disappeared as his own reached the end of the causeway.

The driver pulled up on the shoulder and shut off the engine. After a long silence, someone asked, “Where was it going?”

“Same place we are, I suppose,” the driver answered, turning on the engine again and steering the bus back onto the highway. “We’re going to be late,” he added.

“What are we going to do about this?” the woman behind him asked loudly.

After a moment the driver picked up his mike and said over the speaker. “Folks, we saw a ghost—I guess. Don’t know what else to call it, or who’d be interested in hearing about it. Each of you can do as you wish, but leave me out of it. I’ve got a wife and two kids to support, and I had to move up here from Texas to get this job when the strike started. I’d forget it if I was you. What good can it do you, or anybody, to talk about it? Maybe it was just a delusion of some kind. It’ll make you nuts to think about it too much.”

No one answered him. Rick could feel the need in the passengers to accept what the driver had said. There were murmurs of agreement, slowly dying away like bad memories into silence.

Listening to the steady rhythm of the engine and the tires bumping across the seams in the concrete highway, Rick sat back and wondered whether he could feel his doubles as they came and went throughout infinity. He had always been more than a little in love with death, or rather with the vision of absolute, sublime peace; but that rest could never be, and had never been, he now realized. We are forever born and dying in all the infinity of worlds. I am forever, he told himself, because he was always alive somewhere. They were strangers, all those others. He could not know them any better than he could know himself. He could not choose the thoughts and feelings that came into him like invaders to direct his body. Something that he called himself lived at his center, but it was older and more powerful than the self he knew. That self knew what it wanted to do, and there was no way to resist when it took over. He closed his eyes and felt himself deathless.

In the morning he opened his eyes to fall foliage turning on the hills from green to red, yellow to brown, leaves shrinking and drifting to the forest floor, deathless in their individual deaths, and realized that the spring in which he had begun his bus ride was gone. How could he have been so mistaken about the season? And yet the evidence of his eyes was undeniable. He had dreamed the spring, he told himself as the bus neared the city.

The PA speaker crackled. “Can anyone direct me into the station?” the driver asked. “This is my first time on this route.”

Rick got up, went up the aisle and stood behind the driver.

“Take this exit coming up,” he said, “then turn left, cross the bridge, turn right, and that will put you into the station.”

“Thanks,” the driver said.

Rick stood there to make sure there was no confusion, and noticed snowflakes drifting in against the windshield. “That was pretty weird last night,” he said.

“What was what?” the driver asked.

“The two buses.”

The driver shook his head and smiled at him. “We’re the only bus on this route. You okay?”

“What’s today?” Rick asked, looking around at a few of the other passengers. They all seemed unconcerned.

“November 21,” the driver answered. “What did you think?”

Rick took a deep breath and made his way back to his seat, wondering what had happened to him. No one else seemed to be worrying about the November outside, or what had happened last night.

The young mother was combing her hair and staring at her child, who was still asleep in the seats across the aisle. “That was something last night, wasn’t it?” he asked.

She gave him a bored look and said, “I was asleep. We hit something?”

Rick sat down without answering her. Obviously, they had all forgotten. Suddenly he was looking forward to getting on the homeward bus and seeing Rita again, regretting all his violence against her. She was hard to live with, but so was he. She had probably forgiven him by now, and would be waiting for him at the station, as she had done in the past when they had quarreled. He sat back and waited for the bus to pull into the station, anxious to get off and take the return coach home.

As the bus rolled to a stop, he got up, hurried down the aisle, and staggered out into the arms of two uniformed cops.

“Richard Barrow?” the big one asked, grabbing his wrist.

“Yes,” he said, as the shorter cop took his other hand.

“You’re under arrest for the murder of Rita Malthus,” the tall cop said, slipping on the first handcuff.

“What?” he asked, stunned. “But it wasn’t me.”

“Oh, yeah?” the short cop asked.

“It was... the other one,” Rick said, remembering the spring outside the windows.

“No kidding?” the tall cop said. “Then you have nothing to worry about.”

Rick began to struggle as his hands were brought together and the second cuff snapped shut. “Ask the driver. It wasn’t me!” he shouted, choking on the words. “Ask him!”

“Don’t worry, buddy,” the short cop said, smiling at him. “We’ll ask the driver. We’ll ask everyone.”

“He’ll tell you,” Rick said, feeling his throat go dry as they began to lead him away. He looked over his shoulder for the driver and saw the Hasidic man and his son staring at him as they stepped off the bus. The young mother, child in arms, was just behind them, chewing gum—

—and he saw Rita’s strangled body in his arms, a minute after she had told him about the phone call from a pregnant Tess—

“It was spring earlier today,” he tried to say loudly but couldn’t. Sweat ran down his back, and he saw his guilty double arriving here, free of his crime, and taking the bus home to an unsuspecting Rita, to kill her again. He was in the station right now somewhere, waiting to board.

“You’ve got to stop him!” Rick cried, tearing the words out of his throat. They came up like razors. Hot blood burned through his belly and spread into his guts. A fist closed around his heart, and he staggered, but two cops held him up. “You hav

e to stop him,” he repeated weakly.

“Don’t worry, buddy,” the tall cop said coldly. “We’ve got him.”

The Alternate

“DIDN’T YOU JUST COME BY HERE A FEW MINUTES AGO?” the grocer asked as the register ground out the receipt.

Bruno Lumet looked up from his wallet, one finger still in the billfold, and said, “No, I don’t think so. Oh, and give me a box of that mint tea behind you.”

The grocer shook his head, reached back and grabbed the tea from the shelf behind him, then entered the additional purchase. He was scowling when Lumet handed him the money and took his change, dropped the box of tea into the grocery bag as he picked it up, and went out the door without his receipt.

As he walked up the street toward his apartment house, the morning sun seemed too warm on his back, the trees too green for autumn, the sky too blue after his night shift at the newspaper. The effort of making the stories fit the columns had wound him up; it was like trying to make bad paintings fit the wrong frames. At the start of the week a paperback house had rejected his suspense novel because it had been too short, they said, dashing his hopes of quitting the paper; and they had not asked him to expand the novel, which only meant they hadn’t much wanted it at any length. He would have to remail it to the next publisher on his list before he went to bed this morning.

In front of his house he met the milkman coming down the steps with a basket of empty bottles.

“Good morning, Mr. Lumet,” he said. Lumet nodded to him and went up to the front door. “Say, Mr. Lumet,” the milkman said from the sidewalk, “didn’t I see you at the sports shop last night about nine?”

Lumet turned around and said, “I was at work, Harry, so how could it have been me?”

“Really? You didn’t say hello when I did, so I thought maybe I’d delivered some bad milk, or something.”

“Wasn’t me, Harry, and I’m not mad at you.” Irritated, he turned, went through the front door, and up the one flight to his apartment. He stumbled tiredly down the hall and entered by the kitchen door, letting it slam behind him.

He unpacked the groceries on the table and put them away in the refrigerator and into the cupboard over the sink. Then he went out into the living room and through to his bedroom, where he took off his raincoat and hung it up on the standing rack. He pulled off his tie and sweater and hung them on the chair by the window, then wandered back out into the living room and sat down on the sofa.

All through these ordinary actions of coming home after work he had felt distant from himself, as if he were watching another person’s daily rituals. For a moment, it had seemed to him that he did not know the milkman. Now, as he sat in his small living room, nothing seemed right. Objects, both near and far, seemed too clear around the edges, as if he were looking at them through color-corrected, deep focus lenses. The green rug was too vivid. On the coffee table the partly opened brown paper package of his book manuscript looked too heavy, the string pulpy where he had cut it.

He told himself that he was tired, and irritated by people insisting that they had seen him elsewhere. At work, June from distribution had asked if he had parked his new car next to hers, even though he had always used public transportation. Felix, the city editor, had asked him if he was planning to quit the paper, and had gazed at him strangely, but had not claimed to have seen him somewhere else. Maybe there was someone who looked like him; after all, the grocer and milkman were not drunk or blind. The look-alike was probably getting it from his end also. Maybe he should put an ad in the paper to clue him in.

He got up and went back into the bedroom, not having the energy or the heart to get his manuscript ready to remail. He’d do it tomorrow.

He had stripped down to his underwear, visited the bathroom, and was getting into bed when he heard a knock on the door. He put on his torn, red robe and went out to the front door.

He opened up and saw that it was the caretaker.

“Mornin’, Mr. Lumet, but I had to come and ask...”

“What is it, Frank, I’m very tired.”

“Was you home last night?”

“You know I work nights.”

“Well—the guy below you was woke up when you came in stomping at three in the morning.”

“Not me. I was at work.”

“Well—he’s new here, I know, but he said he saw you come in and out, and you was banging around and woke him up before you left. He’s mad. I sleep deep, and didn’t hear a thing, but I had to check with you.”

“Frank, it wasn’t me. I just got in, as usual. It must have been a drunk on the stairs.”

The caretaker sighed. “Okay, Mr. Lumet. That’s what I’ll tell him. But it’s okay with me if it was you, so keep it down. If it was you.” He smiled, then turned and went down the stairs.

Puzzled, Lumet closed the door, went back to the bedroom, took off his robe and threw it on a chair. His brain refused to shut down as he got into bed. Maybe someone had been here. The lock was no great shakes. He had opened it himself once with a credit card...

After tossing and turning for an hour he knew that he would have no peace until he had checked the entire apartment. He got up and put on his robe, went out through the living room, into the kitchen and into the bathroom. The door was closed, but he now remembered finding the door open and the sun bright in the frosted window when he had come home. He couldn’t be sure.

Opening the door, he went in and checked the medicine cabinet. He was out of aspirin, but there was otherwise nothing out of the ordinary. He closed the cabinet door and went out to the kitchen. The beer and wine were still there in the refrigerator. He reached in and took out the opened bottle of red wine. It slipped out of his hand and shattered on the tile floor. He cursed as a pool of red liquid crept around his bare feet, thinking of the man downstairs, but he was unlikely to complain about daytime noise. Lumet left the kitchen, promising himself to clean up the mess later.

After a few minutes in bed he began to hear the sounds of early cars starting in the street; more distant noises seemed to arrive with the increase of daylight filtering in through his closed curtains. He closed his eyes and relaxed, and listened to his heartbeat in moments of silence as he tried to reduce to unimportance all the frustrations of his recent months. It would be restful, he imagined, to accept his life at the paper and no longer see it as a prelude to a more demanding existence as a human observer, a writerly seer, who would happily baffle most people...

He had a sudden, wild impulse to look under his bed. The command had been waiting for him, somewhere behind his free will, telling him that under the bed was the one place he would never look because he was an adult. Was he falling apart after a few minor irritations and one editorial rejection?

Finally, he accepted that he would look under the bed. It was part of human irrationality to remain unconvinced, even in daylight. Seeing was believing, and so much stronger than any line of reasoning, even when reason was right and could dispense with sight, and he hated the proud child in himself for giving in.

He rolled to one side of the bed, put his head over the side, and saw layers of dust that would have to be cleaned up. He tried to breathe gently, reluctant to stir up too much dirt. There was nothing under the bed except dust and dust devils, happily still, not to be disturbed on pain of sneezing.

He began to cough, and started to pull his head back up when he saw something taped to the springs. He stared at it, slowing his breathing. You knew it was there all the time, he told himself, you knew. But how did you know?

He got out of bed carefully, suddenly proud of his craft and powers of observation. He went down on all fours and put his head and shoulders under the bed. The thing looked like some kind of canister. There was a small dial on it. He touched it carefully. Some mechanism was working inside. He felt it in his fingers.

He got out from under the bed and went to the dresser to get a pair of scissors. Then he crawled under the bed again, cut the tape that held the thing to the

springs and grabbed it with one hand. Dropping the scissors, then holding the thing carefully, he slid out from under the springs, stood up slowly, and sat down on the edge of the bed.

He coughed a few times to clear his throat. There was no doubt about it. Someone had come into his apartment last night and attached this thing to the bedsprings.

He put the cylinder down on the blanket and stood up, realizing as he looked at it that it seemed to be a gas canister, timed for release while he slept.

He leaned close, looked at the small dial, and smiled at his own cleverness as he touched the setting and brought it back to zero. The barely audible clock stopped. He stared at the object, wondering if he had made some kind of mistake, and this was some kind of insect repellant. It seemed too easy to find, but then again perhaps no one had expected that he would ever have time to find the canister before it went off.

It made no sense. Who would want to kill him? Maybe a story of his in the paper had angered someone. He had done a few society announcements, but nothing that might anger a reader. A crank might take offense at anything, he told himself, then wondered if he had a box that would hold the canister, so he could take it down to the police station.

His whole body now ached from tension and tiredness. He should have been asleep by now, but he was wide awake, asking again who would want him dead. Maybe the thing was just a harmless joke? But he had no close friends in Boston. They were all out in California. Had one of them stopped by?

As he stared at the canister, it began to seem very familiar. He stared at it in fascination. It was all so perfectly obvious, and impenetrable at the same time. Its presence made him inexplicably angry at himself...

The phone rang, but he did not hear it until its chaotic insistence began to seem threatening. Was his enemy calling to see if he was unconscious, or dead? He ignored it and hurried to his closet to find an empty shoebox.

He opened the door and saw, in one frozen moment, the crossbow release with a whoosh, followed by a crunch as the bolt pierced his breastbone. He fell back as the steel bow shook where it had been attached to the wall. The phone was still ringing. He lay on his back, listening, hoping that it would not stop, clutching the bolt in his chest. The phone stopped. He heard his own labored breathing and felt the blood pumping out of him into his hands...

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time Stranger Suns

Stranger Suns Black Pockets

Black Pockets Brute Orbits

Brute Orbits Cave of Stars (Macrolife Book 2)

Cave of Stars (Macrolife Book 2) Macrolife

Macrolife Empties

Empties Heart Of The Sun Star Trek 83

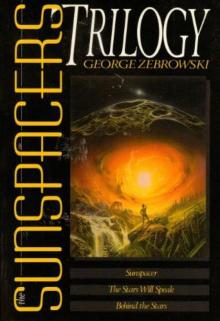

Heart Of The Sun Star Trek 83 The Sunspacers Trilogy

The Sunspacers Trilogy